Cite as: Cedefop; Ministry of Education and Children (2022). Vocational education and training in Europe - Iceland: system description [From Cedefop; ReferNet. Vocational education and training in Europe database]. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/vet-in-europe/systems/iceland-u2

General themes

Summary of main elements ( 1 )

The Icelandic vocational education and training (VET) system originates from the time when Iceland was still part of the Danish kingdom. At that time, apprentices learned from their masters by working alongside them. Gradually, schools took over parts of the training and more theoretical subjects were added. Workplace learning is still important, and the journeyman's exam is centred on demonstrating skills learners have acquired.

Almost all VET is offered at upper secondary level (ISQF 3/ EQF4), where studies at school and workplace learning form an integral part. Study programmes vary in length from 1 school year to 4 years of combined school and workplace learning. Enterprises responsible for training need official certification and training agreements with both the learner and the school, stipulating the objectives, time period and evaluation of the training. Most learners in workplace learning receive salaries, at an increasing percentage of fully qualified workers' salaries. Companies training learners can apply to the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture for a subsidy to fund training.

Several qualifications are offered at upper secondary level; some of these are preconditions for holding relevant jobs. The most common are journeyman's exams but there are also exams for healthcare professionals and captains and engineers of ships and planes. In other professions, a VET degree is not a precondition for employment, but graduates enjoy preferential treatment for the jobs they are trained for.

A few VET programmes are available at post-secondary non-tertiary level (ISQF 4/EQF 5), including tourist guides and captains at the highest level. Certificates for all master craftsmen are also awarded at this level. These programmes last 1 to 2 years and lead to qualifications giving professional rights.

Learners with severe learning difficulties are offered special programmes at mainstream upper secondary schools. Several VET pathways leading to a diploma give these learners the potential to continue their education.

The overall emphasis of the education system is to keep its structure simple and understandable, so learners can move relatively easily between study programmes. They can finish upper secondary school with a vocational and a general degree (matriculation exam), the prerequisite for higher education. VET learners who have not passed the matriculation exam can attend further general education to qualify.

Courses which give study points at upper secondary schools must be approved by an official validation body, according to standards approved by the education ministry.

Upper secondary schools need to submit descriptions of new study programmes to the education ministry. Approved programmes become part of the national curriculum guide. When formulating ideas for new study programmes, schools cooperate closely with occupation councils, which form the link between the ministry and the labour market.

Iceland has one of the highest lifelong learning participation rates among those aged 25 to 64 in Europe (20.3% in 2020). Adult learning is available in upper secondary schools (day classes or special adult evening classes), 11 lifelong learning centres, training centres owned and operated by social partners for skilled workers in certain trades, and in numerous private training institutions. Two institutions owned by employer and employee organisations offer courses for journeymen and masters of trades in the latest technology. For the healthcare sector, retraining courses are offered by universities and there are specific training institutions for several professions. Labour agreements reached in 2000 established specific training funds for employees; both employees and employers pay a certain percentage of all salaries into these funds and both parties can apply for funding towards training.

Distinctive features ( 2 )

Study programmes vary in length from 1 school year to 4 years of combined school and workplace learning.

Participation in VET of young people aged 15 to 24 is among the lowest in Europe at 21.8% in 2021. Looking at all upper secondary learners, however, the proportion is around 32.9% vis-à-vis general studies; this reflects the higher average age of VET learners, many of whom had enrolled in general studies before switching to VET programmes.

Most learners in workplace learning receive salaries; enterprises involved in training can apply to the education ministry for a subsidy to fund the training.

The Upper Secondary Act of 2008 called for VET programmes that better respond to labour market skill needs. The act, as well as the Icelandic national curriculum guide for upper secondary schools, provides, since 2011, for a decentralised approach in designing study programmes and curricula. Upper secondary schools are entrusted with great responsibility and enjoy autonomy in developing study programmes both in general education and VET, combining learning outcomes, workload and credits. Focus is on flexible schedule, in the balance between general subjects and occupational specific skills, and can vary between different VET programmes. However, learning pathways must be accredited by the Directorate of Education on behalf of the education ministry.

In 2014, the education ministry published the White Paper on education reform. Following this publication, the education ministry, the Federation of Icelandic Industries and the Association of Local Authorities contributed to more visible and accessible VET that is also more attractive to young learners. In February 2020, the education minister, along with the chairwomen of the Federation of Icelandic Industries and the Association of Local Authorities, introduced a strategy and priorities on strengthening Icelandic VET. Among the priorities introduced were new policy proposals such as:

- transferring the responsibility for finding apprenticeship contracts from learners to VET schools. When the digital logbook is fully implemented, schools will be responsible for finding work placements for learners;

- VET learners should have the same access to tertiary education as learners succeeding in matriculation exams;

- easier access to qualified guidance and counselling in lower and upper secondary schools;

- making access to VET in rural areas more flexible;

- analyse future infrastructure needs for VET schools;

- simplify VET governance in Iceland.

The Icelandic digital VET logbook project began in 2019, with an aim to launching it online gradually. The first learners started using the logbook on 26 August 2021.

The digital logbook contains descriptions of skills and competence requirements that the learner must have acquired at the completion of learning ( 3 ).The learner, as well as the trainer, record in the logbook all details of the teaching process and the knowledge, skills and competences acquired for the job at the workplace. In the end, the teacher or the institution must certify each step of the teaching process and that the specific competences have been achieved.

This action plan and some of the proposals are already implemented but the challenges posed by Covid-19 have redefined many priorities within both the ministry and the Parliament, possibly delaying some implementation measures.

Population in 2020: 364 134( 4 )

It increased since 2015 by 10.6%. According to national data the proportion of foreign citizens was 13.9% of the entire population in late 2020( 5 ).

The average age of the Icelandic nation is increasing, from 36.4 years in 2010 to 38.4 years on 1 January 2021( 6 ).

The old-age-dependency ratio is expected to rise from 22 in 2021 to 45 in 2070.

Population forecast by age group and old-age-dependency ratio ( 7 )

Source: Eurostat, proj_19ndbi [Extracted 7.5.2021].

Icelandic VET participation rates have for many years been low compared to European rates and the proportion has been slowly decreasing in recent years, as well as the total number of learners at upper secondary level. The average age of the nation is increasing (from 36.9 years in 2012 to 38.4 years on 1 January 2021)( 8 ) but the number of inhabitants has also been increasing for over 100 years, with the exception of 2009 (due to emigration in an economic crisis). This may suggest a demographic impact on numbers of learners at upper secondary level, but does not explain the low ratio of learners choosing VET.

The following table shows the registration numbers of IVET learners between the years 2005-21( 9 ):

Registration numbers of IVET learners for the years 2005-20

|

Year |

Registered IVET Learners |

Year |

Registered IVET Learners |

|

2005 |

860 |

2014 |

877 |

|

2006 |

925 |

2015 |

638 |

|

2007 |

854 |

2016 |

636 |

|

2008 |

896 |

2017 |

546 |

|

2009 |

949 |

2018 |

545 |

|

2010 |

769 |

2019 |

558 |

|

2011 |

732 |

2020 |

642 |

|

2012 |

752 |

2021 |

617 |

|

2013 |

739 |

Source:Directorate of Education

Most companies are small- and medium-sized (less than 250 employees). They constitute 99% of all companies in the country( 10 ).

Main economic sectors for the year 2020.

In terms of export revenues the main economic sectors are ( 11 ):

- manufacturing industry (30%);

- fisheries (27%);

- tourism (11%).

These sectors are all heavily dependent upon labour with VET qualifications, such as chefs, electricians and marine captains.

The labour market is considered flexible in terms of labour mobility.

The Icelandic economy can be defined as small but open with a well-established and regulated system of cooperation between social partners and the government, with the social partners negotiating through collective bargaining to control wage levels and influence prices.

Holding a VET qualification is highly valued by the labour market. However, a certificate is legally necessary only for certified trades such as electricians, masons, builders, plumbers etc.

Total unemployment ( 12 ) (2020): 4.7% (6.2% in EU-27). It has increased by 2.4 percentage points since 2016( 13 ).

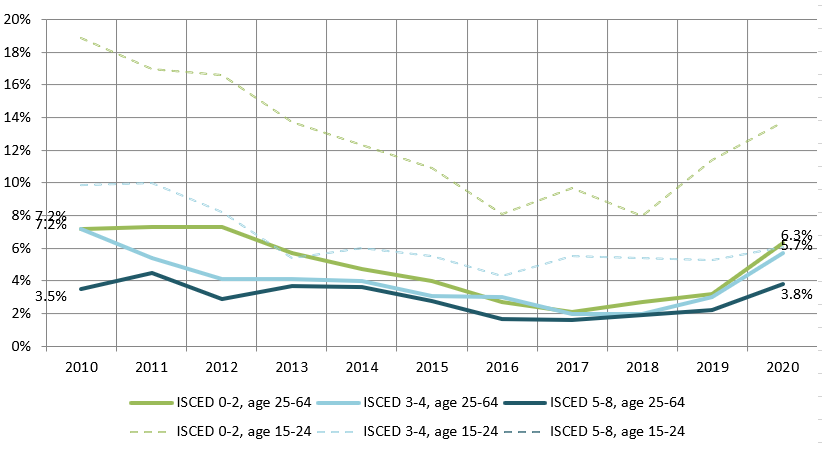

Unemployment rate (aged 15-24 and 25-64) by education attainment level in 2010-20

NB: Data based on ISCED 2011; breaks in time series; low reliability for ISCED 3-4, age 15-24 and ISCED 5-8, both age groups.

ISCED 0-2 = less than primary, primary and lower secondary education.

ISCED 3-4 = upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education.

ISCED 5-8 = tertiary education.

Source: Eurostat, lfsa_urgaed [extracted 6.5.2021].

Unemployment rates are only slightly higher than in the pre-crisis period. For people with medium-level qualifications, including most VET graduates (ISCED levels 3 and 4) aged 25-64, it is 1.5 percentage points lower in 2020 compared to 2010 (5.7% in 2020 against 7.2% in 2010) ( 14 ).

Despite this, the ever-growing demand for more qualified personnel will have an impact not only on people with low qualifications but also on VET graduates as they will need to upgrade their skills.

Employment rate of 20- to 34-year-old VET graduates increased from 92.3% in 2016 to 96.8% in 2017.

Employment rate of VET graduates (20 to 34 years old, ISCED levels 3 and 4)

NB: Data based on ISCED 2011; breaks in time series.

ISCED 3-4 = upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education.

Source: Eurostat, edat_lfse_24 [extracted 6.5.2021].

The increase (+4.5 pp) in employment of 20- to 34-year-old VET graduates in 2016-17 was higher compared to the decrease in employment of all 20- to 34-year-old graduates (-5.3 pp) in the period 2016-20 in Iceland( 15 ). Data on the employment rates of VET graduates for Iceland are available up until 2017.

The share of the population aged up to 64 with higher education (43.7%) is higher than the EU-27 average, and the share of people with a low qualification or without a qualification is among the highest in the EU. The share of people with a medium qualification (ISCED levels 3 and 4), including those in VET, is one of the lowest in the EU.

Population (aged 25 to 64) by highest education level attained in 2020

NB: Data based on ISCED 2011. Low reliability for 'No response' in Czechia, Iceland, Latvia and Poland.

ISCED 0-2 = less than primary, primary and lower secondary education.

ISCED 3-4 = upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education.

ISCED 5-8 = tertiary education.

Source: Eurostat, lfsa_pgaed [extracted 15.6.2021].

Share of learners in VET by level in 2019

|

lower secondary |

upper secondary |

post-secondary |

|

not applicable |

28.4% |

98.7% |

NB: Data based on ISCED 2011.

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_enrs01, educ_uoe_enrs04 and educ_uoe_enrs07) [extracted 6.5.2021].

Share of initial VET learners from total learners at upper secondary level (ISCED level 3), 2019

NB: Data based on ISCED 2011.

Source: Eurostat, educ_uoe_enrs04 [extracted 6.5.2021].

Share of initial VET learners from total learners at upper secondary level in Iceland (ISCED level 3), 2015-21

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|

Theoretical Studies |

2777 |

2800 |

2813 |

2795 |

2880 |

3050 |

2987 |

|

Vocational Studies |

638 |

636 |

546 |

545 |

558 |

642 |

617 |

|

Preparatory Studies |

584 |

684 |

615 |

562 |

607 |

532 |

481 |

|

Special segregated study programme |

147 |

185 |

163 |

203 |

198 |

194 |

231 |

|

Share of Initial VET Learners |

10.4% |

10.1% |

8.9% |

8.9% |

8.9% |

10.0% |

9.7% |

Source: Directorate of Education.

Presently (autumn 2021), almost two thirds (67.6%) of those who choose VET are males, dominating many of the most popular study programmes, such as for various electrical, building and mechanical studies. Females, on the other hand, dominate popular study programmes such as for social service and health care assistants, as well as hair styling and cosmetology.

For the past 5 semesters the distribution between males and females entering into electrical and mechanical studies, has been as shown in the following table:

Distribution of males and females entering into electrical and mechanical studies, autumn 2019 to autumn 2021

|

Total |

Females |

Males |

|

|

1.10.2019 |

5747 |

1980 34.4% |

3767 65.6% |

|

1.3.2020 |

6237 |

2089 33.5% |

4148 66.5% |

|

1.10.2020 |

7036 |

2394 34.0% |

4642 66.0% |

|

1.3.2021 |

6945 |

2322 33.4% |

4623 66.6% |

|

1.9.2021 |

7127 |

2365 33.2% |

4762 66.8% |

Source: Directorate of Education

In the above table, the percentages shown represent the ratio of total learners, as opposed to the ratio of IVET learners.

The share of early leavers from education and training has decreased from 19.7% in 2011 to 14.8% in 2020. It is higher than the EU-27 average of 10.2% in 2020.

Early leavers from education and training in 2011-20

NB: Share of the population aged 18 to 24 with at most lower secondary education and not in further education or training; break in series.

Source: Eurostat, edat_lfse_14 [extracted 06.05.2021] and European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/edat_lfse_14/default/lin… [Accessed 14.11.2018].

Dropout rate from VET (%)

In 2016 (latest data available), the dropout rate from VET was a staggering 37.5% ( 16 ). No doubt a part of this group will return and finish their study programmes at some point, as the average graduation age in VET is around 27 years old.

Lifelong learning offers training opportunities for adults, either employed or unemployed.

Participation in lifelong learning in 2009-20

NB: Share of adult population aged 25 to 64 participating in education and training.

Source: Eurostat, trng_lfse_01 [extracted 6.5.2021].

Participation in lifelong learning is high (20.3% in 2020) and above the EU-27 average but has slightly decreased since 2019 (- 1.9 pp).

An important feature in terms of upgrading the skills of employees (and, therefore, of participation in lifelong learning) is that in 2017 (latest data available), 35% of employees received some kind of training ( 17 ).

The education and training system comprises:

- preschool education (ISCED level 0);

- integrated primary and lower secondary education (EQF levels 1-2, ISCED levels 244) (hereafter basic/compulsory education);

- upper secondary education (EQF 4, ISCED levels 344, 351, 353);

- post-secondary non-tertiary education (EQF 5, ISCED levels 453, 454);

- higher education (EQF levels 6, 7, 8, ISCED levels 554, 665, 766, 768, 864).

Compulsory education starts at the age of 6 and includes 10 years of basic education (or until June of the year a learner reaches the age of 16).

Integrated primary and lower secondary education is the responsibility of the municipalities.

Upper secondary education (either general or vocational) is steered by the State. Only a few of the 37 upper secondary schools do not offer VET programmes.

Post-secondary non-tertiary education is offered for limited specialties (e.g. tour guides and masters of crafts).

Higher education is in line with the Bologna process offering 3-year bachelor, 2-year master and 3-year PhD programmes.

Almost all initial VET in Iceland is in certified trades and built on an apprentice system, where most of the education takes place in school, but workplace training is also necessary. The duration of the time spent in school and the time spent at the workplace varies between programmes and branches. In addition, there is a small number of VET programmes where all the education and training takes place in school and are not certified trades, such as in computer technology and various arts.

The most common duration of VET studies in certified trades is 4 years. An example would be the electrician programmes, which are either 6 semesters in school and 48 weeks in apprenticeship, or 7 semesters in school and 30 weeks in apprenticeship, after which time the pupil is ready to complete a journeyman's examination. An example of a shorter programme that does not lead to a journeyman's examination is a cook programme with 2 semesters in school and 34 weeks in work-based training, or a social care assistant programme comprising 5 semesters, of which the last 2 to 3 take place in work-based training as part of a comprehensive reform of the Icelandic VET system. With this new regulation ( 18 ) the exact timeframe for workplace learning will not be determined at the outset. Instead, the length of the on-the-job training will be determined by how quickly the learner masters a predetermined set of skills. Thus, the focus will be on competences gained in the workplace, not the length of time spent there. Competence factors have been defined for each subject and the student needs to master the elements specified therein. The on-the-job training will be much more competence-driven than before. Learners will be able to graduate earlier instead of being held up, waiting for the appropriate apprenticeship to come along.

VET at post-secondary non-tertiary level is mostly composed of master of crafts' programmes where a journeyman's certificate (in the relevant study programme such as electrical, building or mechanical studies) is a prerequisite for enrolment.

Certified tradesmen (with a journeyman's examination) can also enter (90 ECTS) diploma studies in construction, mechanical or electrical engineering at tertiary level, earning them the professional title of a certified technician.

Continuing VET (CVET) programmes are available for adults and are usually offered by:

- institutions( 19 ) owned by social partners. Courses offered are aimed at upgrading skills. These courses are usually of short duration. People in the labour market with VET qualifications can get financial support from the social partners' training funds for these courses;

- other continuing VET centres ( 20 ), which are much smaller than the social partners' institutions and offer more specialised training.

Workplace training is also offered to employees mainly on security, environmental protection, new working techniques, etc.

According to the framework legislation on upper secondary schooling, a prerequisite for doing qualified VET workplace training is having a contract with a company that is willing and able to offer training in a VET subject. Many prerequisites for such a contract to be signed must be met, including that of the workplace having a certified master in the trade in question.

Two types of contracts are possible:

- a contract between the school and the company, in which the training content must be made as per regulation issued by the education minister, and which contains detailed provision concerning contracts for on-the-job training;

- a traditional apprenticeship contract between the company and the learner, stipulating the rights and obligations of the workplace and the learner respectively, as well as the objective of the training, quality control and the handling of possible disputes. The learner becomes an employee and receives a marginal salary during the training, in line with labour market agreements where the number of working hours is also set.

For several trades, the education ministry has allocated the overall management of the training contracts to a common education centre portal hosted by IDAN education centre( 21 ), which offers continuous education for several VET sectors, where contracts have been streamlined and modularised and guidelines issued to workplaces. Still in production in summer 2019 is a digital VET logbook where the student in question, as well as the trainer, record all details of the teaching process and the knowledge, skills and competences acquired for the job at the workplace. The digital logbook system project started in autumn 2019. In the end, the teacher or the institution must certify each step of the teaching process and that specific competences have been achieved. The Icelandic digital VET logbook project was launched gradually online in 2021, and presently (autumn 2021) it contains around 20 trades ( 22 ).

The length of the workplace training varies from 3 to 126 weeks, depending on the VET study programme. The reasons for this difference are first and foremost: the overall length of the programme on the one hand, and the tradition in each sector on the other. Similar training takes place for professionals in electricity and electronics at Rafmennt VET centre, i.e. the VET centre which specialises in training for electricians.

Learn more about apprenticeships in the national context from the European database on apprenticeship schemes by Cedefop: http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/data-visualisations/apprenticeship-schemes/scheme-fiches

Education is steered centrally by the education ministry. The ministry oversees and provides curriculum for all school levels, including VET.

All upper secondary schools have 'school curricula' where education aims, intended learning outcomes, assessment, content and the connections between these elements are listed.

New VET study programmes are proposed by the upper secondary schools, in cooperation with the occupational councils (which are composed of representatives of the relevant social partners, i.e. trade unions and employers' associations and professional associations). The initiative is often that of the occupational councils, which also define the quality, competences, skills and knowledge requirements and work descriptions. The Directorate of Education liaises between the two and the education ministry, which confirms new study programmes.

The main principle for funding the upper secondary school system and VET is that the education ministry makes a contract with each school concerning the number of enrolled learners and then pays a certain amount, based on a formula that considers the actual cost per learner in the relevant subject per year. The amount differs between study programmes and is higher for VET learners in comparison to general education learners. This applies both to public and private schools.

According to the education ministry, the average cost per VET learner is IKR 1 550 000 (approximately EUR 10 070) per year. This is obtained by calculating the weighted mean of the study of and teaching in VET.

The number of VET learners at upper secondary level was 7 129 in 2021 making the total amount around IKR 11.05 billion (approximately EUR 71.8 million)( 23 ), or 0.4% of the expected GDP and 0.0% of the expected government spending( 24 ).

On-the-job training is funded by the companies which train learners, but they can apply for a subsidy from a State-financed workplace training fund ( 25 ). The fund was founded in 2012 and supports companies with a particular amount per learner per week. In 2020, the fund supported companies with IKR 14 000 (approximately EUR 104) per learner per week, supporting in total 19.811 learner-weeks with IKR 277.5 million (approximately EUR 1.48 million).

All apprentices are entitled to salaries during their training periods, albeit much lower than those of the fully qualified staff. In the certified trades, the minimum wage for apprentices ranges from IKR 318 246 (around EUR 2 068) to IKR 342 279 (around EUR 2 228) per month, or IKR 1 989 (around EUR 13) to 2 142 (around EUR 14) per hour (in regular daytime work, otherwise higher), the amount increasing gradually for more weeks at the workplace( 26 ).

Continuing VET (CVET) programmes are usually short in duration and funded either by the relevant workplaces, by social partners, by the State or a combination of two or three of the above to varying degrees.

In VET, there are:

- general subject teachers;

- teachers of vocational subjects;

- trainers at the workplace.

General subject teachers must have a master degree in education from a university.

Teachers of vocational subjects must be masters of craft in the relevant profession and have taken a minimum of 60 ECTS ( 27 ) in pedagogy at a university.

Trainers at the workplace must be masters of craft in the relevant profession.

Although salaries for VET teachers have increased, the teacher population is ageing. Attracting young people to the profession remains a challenge.

Teachers can receive various scholarships to finance further university studies and for work, school visits at home or abroad, conference fees, study leave etc. The official funds are financed by the schools/employers but managed by the teachers' unions. Teachers can apply to the education ministry for up to a year's study leave on full salary, but most teachers are not granted this more than once and then usually only after more than 20 years at work.

Various other options are available, such as scholarships to finance part-time studies or shorter periods of study leave. Teachers are also expected to spend 2 weeks per year in continuous education, outside the school year; they have access to various other funds and options for continuous education on the basis of their wage agreements with the State. Choosing the relevant study programmes, conferences etc. is mostly up to the teachers and trainers themselves, and the programmes and training are provided by lifelong learning institutions (e.g. in the electricity sector) and universities, among others, and via study visits at home or abroad.

More information is available in the Cedefop ReferNet thematic perspective on teachers and trainers ( 28 ).

The role of the Occupational Council is (among other duties) to advise the Minister of Education, Science and Culture, and to provide opinion on the categorisation and division of occupations between the twelve Occupational Councils.

Due to the small size of the labour market, most trades are based on a broad level of competences, so that graduates have a wider possibility of employment. The exams at the end of each study validates whether this is indeed the case. Thus, the studies can rather be termed output based than input based, even though studies are defined in the hours it takes to complete them.

When assessing future skills needs, the twelve occupational councils are the strongest link between the education ministry and industry. The councils operate under the responsibility of the ministry and are composed of representatives of the relevant social partners and trade associations for different vocational trades. Each council has the role to define the needs of a particular trade in respect to the knowledge and ability required, the aims and structure of the education and the curriculum guidelines. The councils often initiate or suggest new VET study programmes or changes to existing ones, but it is up to the upper secondary schools to propose such programmes and the Directorate of Education to liaise between the two, while it is up to the education ministry to confirm new study programmes.

In early 2020 that policy changed and servicing and coordinating the work of the occupational councils was taken over by the Directorate of Education.

Currently, in Iceland, there has not been made systematic estimates or forecasts regarding skills anticipation and needs in the labour market or for certain trades. However, in the Education Policy 2030( 29 ), agreed by the Parliament, and the related action plan, there is a proposal on estimating future need for competences skills in the labour market. This policy involves the education ministry providing comprehensive school services (supporting learners, their parents, the school staff, and school activities), integration of services for the benefit of the learners (an organised and continuous service that aims to promote the learners' wellbeing and is provided to those service providers who are best suited to meet the learners' needs at any given time), tiered support (a comprehensive plan of teaching, practice and support measures in schools aimed at equal opportunities for all), and prosperity services (all services that by law are to be provided by the State or municipalities and take part in promoting and/or ensuring the wellbeing of children).

See also Cedefop's skills forecast( 30 ) and European skills index( 31 ).

Due to the small size of the labour market, most trades are based on a broad level of competences, so that graduates have a wider possibility of employment. The examinations at the end of each study validate whether this is, indeed, the case. Thus, the studies can rather be termed output- based than input-based, even though studies are defined by the hours it takes to complete them.

According to the education ministry's national curriculum guide for upper secondary schools( 32 ), the education institutions may develop new study programmes, although subject to approval and validation by the ministry after consultation with the relevant occupational council, in the case of a VET programme. All upper secondary schools have a school curriculum where education aims, intended learning outcomes, assessment, content and the connections between these elements are listed. Individual schools are responsible for all study programmes they offer but can use study programmes from other schools as well.

Once approved by the education ministry, new study programmes become part of the curricula for upper secondary schools when published in the legislator's legal journal.

The twelve occupational councils, composed of representatives of the relevant social partners and professional associations for different vocational trades, discuss the demand for new study programmes and the need for updating existing ones in terms of: qualifications demands, basic structure, competences, skills and knowledge requirements of work descriptions, which they define and gradually update. Typically, they report the need for new study programmes or updates to existing ones to individual schools or to the directorate for education. The upper secondary schools do, however, have the task of proposing new study programmes or updating them, including the curricula, often at the initiative of the occupational councils but sometimes also at their own initiative based on their estimate of existing demand. The schools' ideas are then put before the relevant occupational council to discuss the desirable qualification demands and structure, and the Directorate of Education liaises between the two before the education ministry finally approves the study programme.

This process can vary, in terms of processes, initiatives and procedures, between schools, occupational councils, individual teachers/trainers and study programmes. It is, however, always a result of a liaison between the schools and the occupational councils, always developed within the framework of the national curriculum guide and always subject to approval of the education ministry.

The education ministry validates the study programmes for all upper secondary education and training, which become part of the curricula for upper secondary schools when published in the legislator's legal journal.

The VET study programmes for all trades are developed in cooperation with members of each occupation's association through twelve occupational councils. Job descriptions, knowledge, skills and competences are gradually revised by the occupational councils.

All upper secondary schools are subject to a quality evaluation performed by outside parties once every 5 years. The quality criteria are defined by the education ministry. The schools are requested to report on their performance according to the ministry's quality criteria (internal evaluation) and the Directorate of Education hires independent consultants to perform a quality evaluation based on the same criteria. The independent consultants' reports are published openly on the Directorate of Education's website, but prior to that the schools are given a chance to respond to a draft report and the consultants may adjust their report accordingly. Follow-up to the evaluation reports is the responsibility of the education ministry and of course the schools themselves.

Training providers must be formally accredited by the Directorate of Education, on behalf of the education ministry, to obtain a licence to teach courses for adults giving credits that can be used for further training at upper secondary schools.

The accreditation is based on the evaluation of the following:

- teaching and learning facilities;

- organisation and supervision of studies;

- curricula or course descriptions;

- the competences of adult education providers, with regard to their knowledge and experience;

- financial issues and insurance;

- the existence of a quality control system focused on adult education.

The accreditation does not entail commitment for public funding to the education provider in question or responsibility for the education and training provider's liabilities.

For several trades, the education ministry has allocated the overall management of the training contracts to a common education centre portal hosted by IDAN education centre( 33 ), which offers continuous education for several VET sectors, where contracts have been streamlined and modularised and guidelines issued to the workplaces.

Real competence validation/accreditation of prior learning( 34 ) is a system organised by the social partners and the education ministry to validate non-formal and informal learning. People who have acquired some skills at workplaces, for example, can get them validated through a formal process, which may shorten their study periods towards. a journeyman's examination in a trade, for example. They also get valuable assistance (counselling and study aid) if they have dyslexia, for example, or other learning problems. Real competence validations are available in several trades. Social partners and the education ministry are working on expanding the offers.

For more information about arrangements for the validation of non-formal and informal learning please visit Cedefop's European database( 35 ).

The Icelandic student loan fund (MSNM) provides a loan for living expenses, according to the general cost of living in Iceland, taking into account the student's social circumstances and place of residences. (This applies to all learners, regardless of whether they are VET learners or learners of general study programmes.) The fund supports VET learners doing vocational training and internships, at upper secondary school level, or upper secondary additional studies for internships, provided that the study programme qualifies for at least the third study skill level, and is not offered at University level. Study loans are only available to learners aged 18 and over.

According to the new Act on the Icelandic student loan fund ( 36 ) the terms for loans to learners are the following:

- the loans are inflation-adjusted, but no interest is applied during the period of studying;

- repayments shall begin 1 year after graduation and provided that the student is under the age of 40, they can choose whether the repayments are income-linked or set out as annuity loans. Learners can choose whether the loans are indexed or non-indexed. Reimbursements are assumed to end before the age of 67. The interest terms of the loans are also based on the interest terms available to the State treasury on the market, plus a fixed charge that is to be reviewed each year, now set at 0.8%.

Notwithstanding the above, the interest rate cap on indexed loans shall be 4% and 9% on non-indexed loans.

In recent years, increased emphasis has been put on vocational and education counselling to help learners choose their study paths, and thus drawing their attention to often less visible VET study and training options where applicable.

On-the-job training is funded by the companies which train learners, but they can apply for a subsidy from a State-financed workplace training fund. The fund was founded in 2012 and supports companies by a particular amount per learner per week. In 2020, the fund supported companies with IKR 14 000 (approximately EUR 104) per learner per week, altogether supporting 19 811 learner-weeks with IKR 277.5 million (approximately EUR 1.48 million). This makes a big difference, especially for small companies which would otherwise not be able to afford training costs.

The education ministry has an ongoing contract with skills Iceland( 37 ), charging this organisation with the responsibility of supervising the Icelandic skills competition every other year, as well as to enable participation of VET learners in Euro Skills.

In recent years, increased emphasis has been put on vocational and education counselling to help learners choose their study paths. For example, at grammar school level VET subjects were introduced in an attempt to increase VET attractiveness. Work is in progress to enhance VET counselling and guidance.

Please see:

- guidance and outreach Iceland national report( 38 );

- Cedefop's labour market intelligence toolkit( 39 );

- Cedefop's inventory of lifelong guidance systems and practices( 40 ).

Vocational education and training system chart

Programme Types

| ECVET or other credits | Up to 240 credits ( 43 ) |

|---|---|

| Learning forms (e.g. dual, part-time, distance) | The programmes are adapted to each individual's skills and needs and are generally a combination of general and vocational studies. |

| Main providers | Upper secondary schools. |

| Share of work-based learning provided by schools and companies | Information not available ( 44 ) |

| Work-based learning type (workshops at schools, in-company training / apprenticeships) | The programmes are adapted to each individual's skills and needs and are generally a combination of general and vocational studies, school-based and in-company practice. |

| Main target groups | Programmes are available for people with special education needs as well as young people and adults, but are especially meant to provide opportunities for young people with special education needs. |

| Entry requirements for learners (qualification/education level, age) | Compulsory education and an official confirmation (provided by a health authority) of a special needs' status. |

| Assessment of learning outcomes | The learners' status is subject to assessment – by formal (such as by examination) or informal means, i.e. via continuous evaluation by teachers of progress made by the learner – throughout his or her study time. |

| Diplomas/certificates provided | Learners finishing this programme receive an upper secondary school diploma of competence (hæfnipróf á framhaldsskólastigi). The composition between general studies and VET varies between individual learners. The diploma is recognised by all relevant authorities but does not entail a professional qualification. |

| Examples of qualifications | Not applicable ( 45 ) |

| Progression opportunities for learners after graduation | These diplomas can entail the potential for the learners to continue their education, at EQF level 4. However, continuation of studies is subject to various forms of assessment. |

| Destination of graduates | Information not available |

| Awards through validation of prior learning | No |

| General education subjects | Yes The programmes are adapted to each individual's skills and needs and are generally a combination of general and vocational studies, school-based and in-company practice. |

| Key competences | Yes The national curriculum guide for upper secondary schools ( 46 ) defines the fundamental pillars of education as literacy, sustainability, democracy and human rights, health and welfare and creativity. These pillars are represented in all curricula, to a varying degree. |

| Application of learning outcomes approach | Yes The curricula are defined with respect to competences, maturity and knowledge. |

| Share of learners in this programme type compared with the total number of VET learners | <1% ( 47 ) |

| ECVET or other credits | 154 to 290 credits ( 48 ), depending on the programme. A journeyman's exam in a certified trade such as an electrician is typically 260 credits (in 4 years), automobile painting is 154 credits (2.5 years) but some food processing trades (e.g. meat processing and baking) are 290 credits (4 years, with 200 credits out of 290 in WBL). |

|---|---|

| Learning forms (e.g. dual, part-time, distance) |

The most common form is a mixture of school-based learning and apprenticeships. Usually a majority of the studies is school based (e.g. 180 credits versus 80 credits in WBL for electricians) but in food processing trades the majority is usually WBL (200 out of 290 credits). |

| Main providers |

|

| Share of work-based learning provided by schools and companies | >=70% |

| Work-based learning type (workshops at schools, in-company training / apprenticeships) |

|

| Main target groups | Programmes are available for young people and adults. The total dropout rate at upper secondary school level is very high but many learners return to VET programmes having started and left general studies earlier. |

| Entry requirements for learners (qualification/education level, age) | Completion of compulsory education (primary and lower secondary) is required for admission (entry is also allowed through validation of adult prior learning). |

| Assessment of learning outcomes | Each course or workplace training module finishes with some sort of an assessment, either theoretical or hands-on. Learners complete their overall studies with a VET exam. They can also opt for a path toward Matriculation exam, in which case the studies may take longer, because they must add general subjects to their list of VET courses. |

| Diplomas/certificates provided | The most common diplomas are certified trades´ school diplomas (burtfararpróf) and journeyman's diplomas (sveinspróf), granting certain professional rights and rights to further VET studies. Other examples from a vast array of terms used include those of a health care assistant (sjúkraliði) and marine engineer (vélstjóri), also granting professional rights and rights for further studies post-secondary non-tertiary level. |

| Examples of qualifications | Mason, hair stylist, health care assistant ( 49 ). |

| Progression opportunities for learners after graduation | Access to VET taught at post-secondary non-tertiary level depends on the completion of an upper secondary level certificate in the relevant subject and requires work experience, the length of which differs much. Prerequisite for admission to higher education is to pass matriculation exams or possibly have one's experience and prior learning validated towards possible missing parts of the formal matriculation exam. |

| Destination of graduates | Information not available |

| Awards through validation of prior learning | Yes People who have acquired some skills at e.g. workplaces can get them validated through a formal process, partly operated by education centres run by social partners, which may shorten their study periods towards e.g. a journeyman's exam in a trade. Real competence validations are available in several trades and social partners and the education ministry are gradually expanding the offers. |

| General education subjects | Yes At least the Icelandic language, English and mathematics form a part of all study programmes, to a varying degree between programmes. |

| Key competences | Yes The national curriculum guide for upper secondary schools ( 50 ) defines the fundamental pillars of education as literacy, sustainability, democracy and human rights, health and welfare and creativity. These pillars are represented in all curricula, to a varying degree. |

| Application of learning outcomes approach | Yes The programmes are based on the occupational councils´ definition of competences, skills and knowledge. |

| Share of learners in this programme type compared with the total number of VET learners | >75% ( 51 ) |

| ECVET or other credits | 120-260 credits, depending on the nature of the programme ( 52 ). |

|---|---|

| Learning forms (e.g. dual, part-time, distance) |

|

| Main providers |

|

| Share of work-based learning provided by schools and companies | >=50% |

| Work-based learning type (workshops at schools, in-company training / apprenticeships) |

|

| Main target groups | Programmes are available for young people and adults. |

| Entry requirements for learners (qualification/education level, age) | Learners must hold a compulsory education certificate. |

| Assessment of learning outcomes | Each course or training module finishes with some sort of an assessment, either theoretical or hands-on. Learners complete their overall studies with a VET exam. They can also opt for a path toward Matriculation exam, in which case the studies may take longer, because they must add general subjects to their list of VET courses. |

| Diplomas/certificates provided | Upper secondary level certificate in the relevant subject (framhaldsskólapróf), not granting professional rights but often granting rights for further VET studies. |

| Examples of qualifications | Film maker, painter, sculptor ( 53 ) |

| Progression opportunities for learners after graduation | Access to VET taught at post-secondary non-tertiary level depends on the completion of an upper secondary level certificate in the relevant subject. Prerequisite for admission to higher education is to pass matriculation exams. |

| Destination of graduates | Information not available |

| Awards through validation of prior learning | No The system of validation of prior learning is mostly connected with workplace / labour market experience and thus not as relevant in these programmes as e.g. in the certified trades. |

| General education subjects | Yes At least the Icelandic language, English and mathematics form a part of all study programmes, to a varying degree between programmes. |

| Key competences | Yes The national curriculum guide for upper secondary schools ( 54 ) defines the fundamental pillars of education as literacy, sustainability, democracy and human rights, health and welfare and creativity. These pillars are represented in all curricula, to a varying degree. |

| Application of learning outcomes approach | Yes |

| Share of learners in this programme type compared with the total number of VET learners | <5% |

| ECVET or other credits | Around 40 upper secondary school credits ( 57 ). |

|---|---|

| Learning forms (e.g. dual, part-time, distance) | Mostly part-time distance learning with several in-school sessions per term. |

| Main providers | Schools |

| Share of work-based learning provided by schools and companies | >=10% ( 58 ) |

| Work-based learning type (workshops at schools, in-company training / apprenticeships) |

|

| Main target groups | Programmes are available for people who have already completed VET studies at upper secondary level, typically a journeyman's exam or certain levels in art programmes. |

| Entry requirements for learners (qualification/education level, age) | Completion of VET studies at upper secondary level, most often a journeyman's exam, plus a certain basic knowledge of relevant computer software (such as Excel, Word and sometimes AutoCAD). Also, relevant upper secondary level in the case of various art programmes. |

| Assessment of learning outcomes | Each course or practical assignment finishes with some sort of an assessment, either theoretical or hands-on. |

| Diplomas/certificates provided | Mostly Master of Craft certificates (iðnmeistari) in the relevant trade (plumbers, electricians, hair stylists etc.). Also e.g. upper secondary examination at various fine and applied art levels (e.g. music at levels 6 and 7) (6. og 7. stig í tónlist), marine engineers (vélstjórar), marine captains (skipstjórar). |

| Examples of qualifications | Master of plumbing, master of building, pianist, textile artist ( 59 ) |

| Progression opportunities for learners after graduation | Access to VET taught at post-secondary non-tertiary level depends on the completion of an upper secondary level certificate in the relevant subject and requires work experience, the length of which differs much. Prerequisite for admission to higher education is to pass matriculation exams. |

| Destination of graduates | Information not available |

| Awards through validation of prior learning | No Validation of prior learning is not available at this post-secondary VET level. |

| General education subjects | Yes The Master of Craft programmes e.g. are largely based on subjects like management, accounting etc. |

| Key competences | Yes Key competences like sustainability and participation in a democratic society are parts of the curriculum guide. |

| Application of learning outcomes approach | Yes |

| Share of learners in this programme type compared with the total number of VET learners | >=10% ( 60 ) |

| ECVET or other credits | 90 ECTS ( 63 ) |

|---|---|

| Learning forms (e.g. dual, part-time, distance) | Distance learning with 2 weekends' school-based sessions per term. |

| Main providers | Reykjavik University |

| Share of work-based learning provided by schools and companies | >=15% (several practical assignments, including one 12 ECTS assignment, usually in-company). |

| Work-based learning type (workshops at schools, in-company training / apprenticeships) | In-company practical assignments. |

| Main target groups | Programmes are available for young people and adults but mainly targeted at people with a journeyman's certificate. |

| Entry requirements for learners (qualification/education level, age) | A journeyman's certificate, or at least having completed its general studies' part, or a matriculation exam. In the former case, some bridging courses may apply, in mathematics, physics, Icelandic and English. |

| Assessment of learning outcomes | Examinations, essays, practical assignments etc., at the end of or during each course. |

| Diplomas/certificates provided | A diploma as a certified technician, plus the right to practice as a Master of Crafts in the relevant trade. |

| Examples of qualifications | Mechanical technician, electrical technician, construction technician ( 64 ). |

| Progression opportunities for learners after graduation | Students can progress to the next level of tertiary education, i.e. to EQF level 6 B.Sc. studies in science and engineering. |

| Destination of graduates | Information not available |

| Awards through validation of prior learning | No |

| General education subjects | Yes Courses include management, law and accounting. |

| Key competences | Yes |

| Application of learning outcomes approach | Yes |

| Share of learners in this programme type compared with the total number of VET learners | <1% ( 65 ) |