Low levels of skills are associated with negative economic and social consequences not just for the individuals and their families but also for the whole economy and society.

The other side of the coin is that investing in education is linked to higher economic and social returns. Thus, empowering low-skilled adults by means of promoting their upskilling and re-skilling must be seen as a priority, especially nowadays that employment and the economy overall is becoming skills intensive.

Low-skilled adults are a highly heterogeneous population, comprising people with very different characteristics and needs including low education (early school leavers); low digital skills; low cognitive skills or medium-high education but at risk of skill loss and obsolescence.

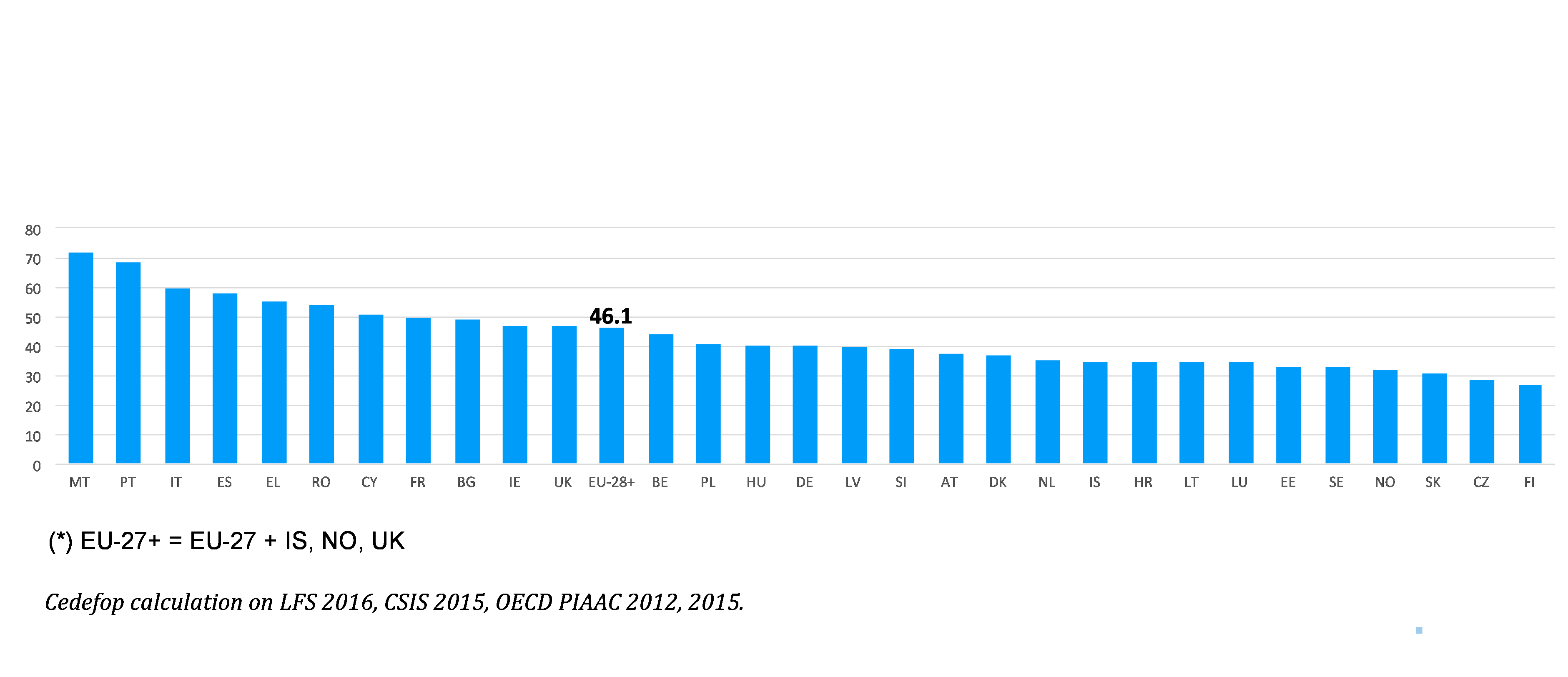

According to 2020 Cedefop estimates, there are 128 million adults in the EU-27 Member States, the UK, Iceland and Norway with a potential for upskilling and reskilling. This represents almost half (46.1%) of the adult population in all these countries.

The estimates paint an alarming picture and hint to a much larger pool of talent and untapped potential than the 60 million low-educated adults usually referred to as low-skilled in the literature.

Chart 1. Low-skilled adults in the EU-27, Iceland, Norway and the UK, 2020

Low-skilled adults often accumulate several vulnerabilities and are furthest away from the labour market or are in precarious jobs and at risk of unemployment, yet they benefit the least from upskilling and re-skilling opportunities. But let’s take a closer look at the challenges and opportunities they face in the labour market.

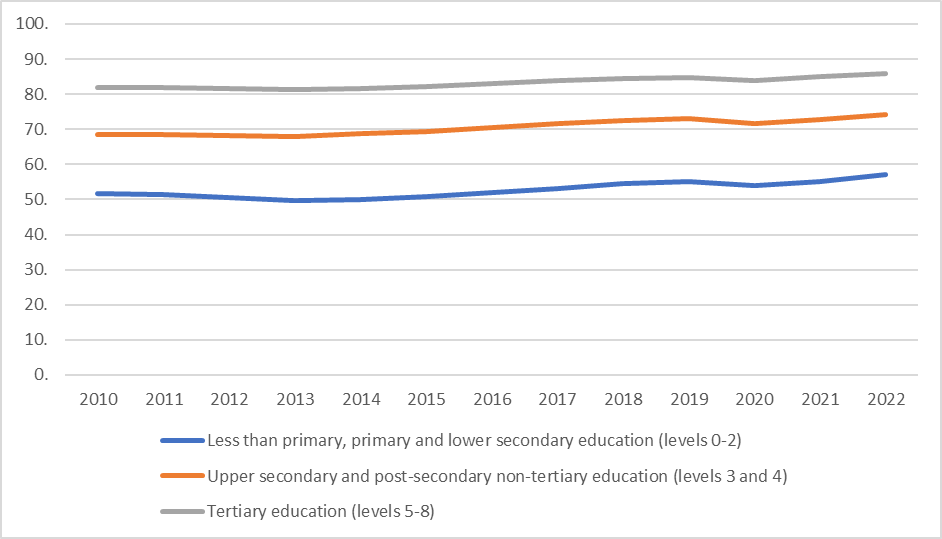

Looking into the state of play of low-skilled in the labour market, one may see that the employment rate of low qualified is considerably lower than the average.

Chart 2. Employment rate of educational attainment level

But even if they are employed, low-skilled adults are often trapped in adverse employment relationships, the so-called precarious employment. Indeed, evidence suggests (Livanos, I. and O. Papadopoulos) the low educated have higher presence in involuntary non-standard employment, meaning that are much more likely to end up working part time or temporarily, despite their preference for full-time and permanent work. And, at the same time, they have much higher shares in work that occurs during unsociable hours, such as evenings, nights, and weekends. There is plenty of evidence (Keller et al., 2009) that such work is linked to various negative health outcomes.

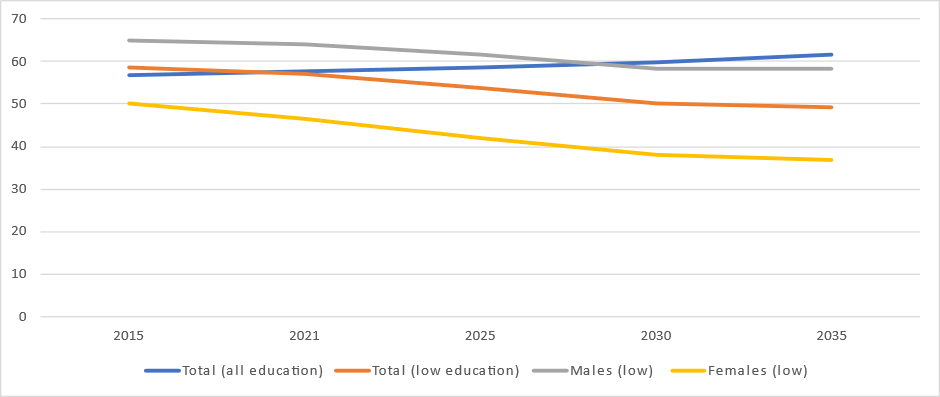

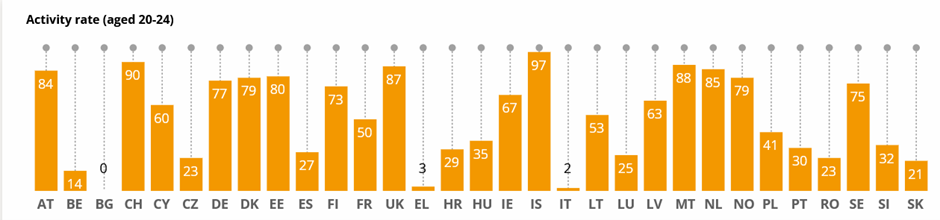

Possibly as a result of the above, the low-educated often refrain from participating in the labour market. Based on Cedefop estimations about future trends in labour market participation, showing the breakdown by gender and the total labour force for people aged 20-24, we see that even though the overall participation rate is due to increase, when we look at the low educated, then this is estimated to decline further to 2035 for both men and women.

Chart 3. Labour market participation rate to 2035 for low-skilled young adults (20-24)

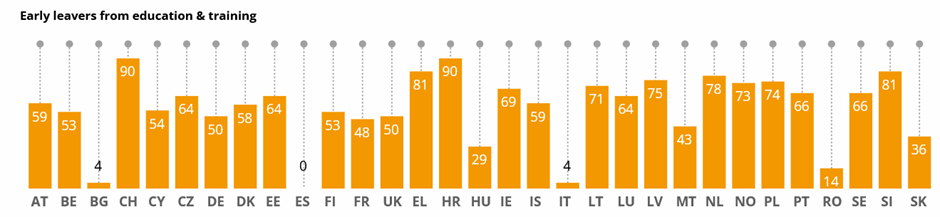

Looking further at how labour market activation varies across European countries, and using data from Cedefop European Skills Index, we may see measurements of labour market activation across member states. On top, we see the index scores about early school leavers and the bottom is about activity rates of young people. The score is shown from a scale from 0 to 100 and the higher is the score the better is the situation of a country.

Chart 4. Labour market activation across EU

It is evident that there are some countries where labour market activation is indeed a big problem, such is Romania, Italy, Spain, Bulgaria where scores are low for both measurements.

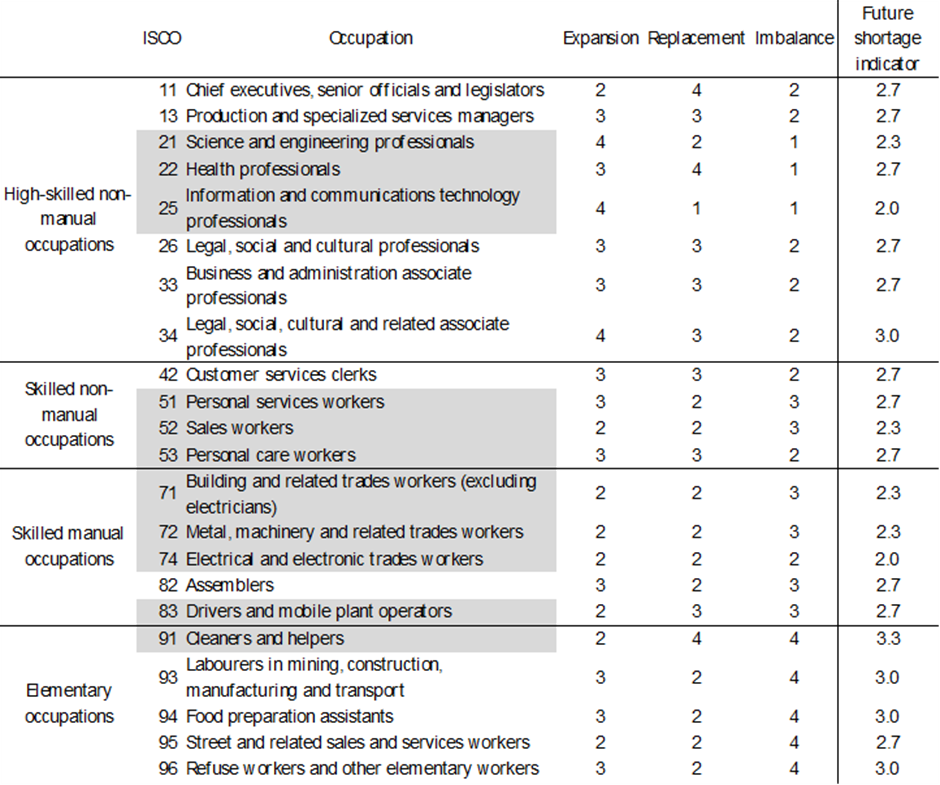

One may question whether all these elements presented above, that is the negative employment outcomes or the falling participation rates, can be explained by the lack of jobs for the low-skilled and whether this situation will get worse in the future, given the digital and green transition.

The below table showing our Cedefop Future Shortage Indicator captures various measures. Based on this, we estimate strong future shortages in low-skilled jobs and one of the reasons behind these shortages is the lack of people available to take up posts as cleaners and helpers.

Thus, labour market activation policies for the low-skilled is in fact essential as it could be a way to mitigate such future shortages. Efforts to increase educational attainment, qualification and skill levels of low qualified are particularly important to make them employable in the labour market.

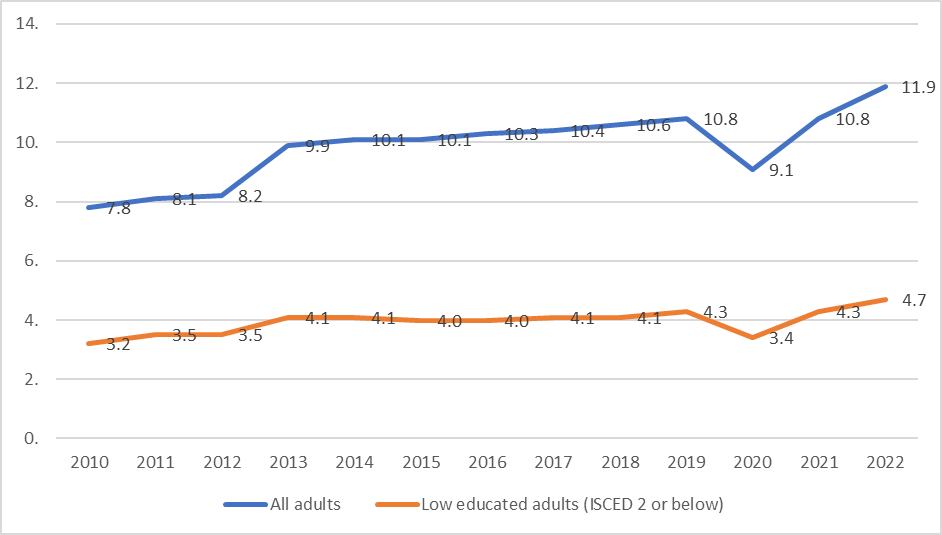

Yet it is observed that their participation in further education and training is considerably below average and it has not grown a lot over recent years.

Chart 5. Participation of low qualified in adult education and training in the 4 weeks prior to the survey (%)

Ensuring that every adult has lifelong opportunities to constantly update and acquire new skills to navigate uncertain times and to thrive in their life and career is vital. This is even more relevant for adults with low skills who struggle in precarious jobs and unemployment.

The European Council adopted in 2016 the Recommendation on “upskilling pathways: new opportunities for adults” putting low-skilled adults into the spotlight of EU and national policies and encouraging Member States to offer upskilling and reskilling opportunities for the low-skilled adult population.

The Recommendation is a turning point in the way upskilling and reskilling is understood, organised and delivered. Developing adults’ skills refers not only to training but also to services such as outreach, career guidance, validation of non-formal and informal learning, which together constitute the pathway to employment, to a higher qualification and to more and better skills. All these services together support the Recommendation’s push for individualised upskilling pathways.

Cedefop plays a very important role in supporting MS to implement the Council recommendation for upskilling pathways. In response to a direct need of Member States and EU stakeholders, Cedefop has developed a unique vision of upskilling pathways for low-skilled adults creating an analytical framework for a comprehensive approach to their upskilling and reskilling by pulling together different resources and creating the right synergies.

Cedefop has also developed practical toolkits aiming both to prevent low skills by tackling early school leaving, and to empower people not in employment, education or training through vocational education and training supporting their reintegration into the labour market.

In these toolkits one can find key intervention approaches and tips to develop own action plans, a plethora of good practices taking place in European countries to get inspiration, as well as several interactive and practical tools designed both for policy makers and education and training practitioners.

This blog article was prepared with inputs from Cedefop experts Livanos I., Psifidou I., Salvatore L. and Serafini M. and presented in the EURoma Management Committee (6-7 June 2023, Brussels) as part of the EU skills year.

Join us to fight against early leaving and prevent low skills in Europe