Microcredentials are increasingly prominent in discussions around education, training and labour market policy. Policymakers, educators and trainers across the world see microcredentials as an innovation with various uses and benefits: a kind of all-purpose solution for the problems confronting education, training and labour market systems. Some have begun to integrate them into existing practice and policy frameworks. But can microcredentials enhance employability, labour market participation and outcomes among end users? Can skills assessments and micro-certificates awarded in specific sectors support individuals in finding work or in improving the match of their skills with their job?

Considering the relative novelty and growing use of microcredentials, evidence of their impact is still scarce. Cedefop’s (2023) evidence shows that to assess the added value of microcredentials fully means observing that value is shaped by both supply and demand side factors. Their relative value varies across national VET systems and industry sectors and is shaped by various factors; the skills intensity and innovation dynamics in sectors of the economy, the governance and configuration of national VET systems, and the role of training in labour market policies. Ensuring employers’ trust in the value of microcredentials remains a key policy challenge.

The existence of digitally enabled learning ecosystems is another key factor affecting whether (digital) microcredentials proliferate in a labour market. Such digitalisation of learning processes further interacts with the extent to which employer trust in the value of microcredentials can be assumed. Cedefop’s (2020) Crowdlearn study, for instance, sought to understand the evolution of learning in the online platform economy, a new, innovative and rapidly growing segment of the labour market. Crowdlearn evidence highlighted the clash taking place between the value of crowdworkers’ qualifications and additional (micro)credentials with other forms of skills validation/screening (Box 1). Several online labour platforms offer freelancers the opportunity to gain digital micro-certificates by passing the platforms’ own skill certification tests. For instance, Upwork offers hundreds of different skill tests on topics ranging from communication in English to graphic design techniques and programming language expertise. Once a test is successfully passed, a digital badge certifying completion is displayed on worker’s profile.

However, the efficacy of such tests in helping to match skills supply with demand seems to be limited. In dedicated qualitative interviews, Upwork’s representatives told Cedefop that internal research found that its clients prefer to use profile introductions, portfolios and job feedback to assess a freelancer’s skills and experience rather than skills certificates alone. Other recent research suggests that skill tests are of limited usefulness in helping new workers enter the market: they certify the worker’s skills but not their general trustworthiness, something that is important in remote work conducted over the Internet by relative strangers (Kässi and Lehdonvirta, 2021). On Upwork, Fiverr, and PPH’s freelancer profile page, for instance, certificates are listed at the bottom, which suggests they have less relative value than other signals of professionalism and trustworthiness such as buyer/client feedback [1]. Many platforms deploy algorithmic skills-matching systems using machine learning, automatically ranking or endorsing specific workers based on the data traces they have and those provided by their clients, and recommending them to potential clients on this basis [2]. A dedicated Crowdlearn survey, which obtained information from a representative sample of online freelancers from four major online platforms, further confirms that specific digital skills tests and certificates were required or helpful in getting platform projects only for about one in four online freelancers.

|

Box 1: Interview with platform worker Julia – ‘I don’t need certification, it’s just paper’ Julia is Italian and 29 years old. She freelances as a translator on Twago and Upwork. In 2011 she was awarded a bachelor degree in interlingual and intercultural mediation from an Italian University. Since graduating, she has focused on work in the communication field, focusing on translations, interpreting, customer care and tutoring of foreign languages as a full-time freelancer. Recently, her freelancing has required her to learn more skills relevant to marketing and business, so she is turning to online courses to build up a skills basis in this and is even considering going back to university for a postgraduate course. 'There are few courses in areas such as writing, copywriting, and digital marketing. I found them on free platform such as Coursera, FutureLearn, Alison, or sometimes I just watch YouTube videos. Yeah.' While Julia does many courses across several different platforms, she does not value the certification that they provide at the end of the course. Rather, she views the certification system as a way for the platforms to generate further income. She does not think that her clients would value a formal certification: her ability to prove that she can complete the task at hand is what is necessary. 'I don’t need certification because it’s just, actually, it’s just a paper. And, so for example, on FutureLearn, you study and you do exactly the same thing as someone else that is going to get the certification. So, you are going to learn the, the same. But, you pay, for example, forty or sixty pounds to get a paper saying that you attended the course online, so it’s not very useful, I think.' Source: Cedefop Crowdlearn qualitative interviews; see Cedefop (2020) |

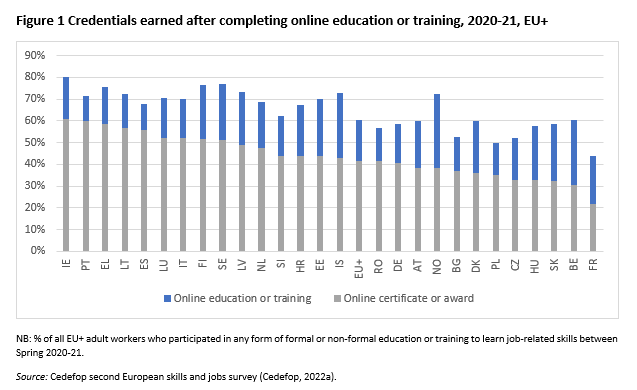

While the online platform economy is only a minor part of the overall labour market, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated such digitally mediated forms of learning and certification for many workers. Evidence from Cedefop’s second European skills and jobs survey (Cedefop, 2022a), a representative survey of 46k adult workers in 29 European countries (EU27 and Iceland, Norway) carried out during the first year of the pandemic, highlights that 38% of the EU+ workforce undertook at least one online education and training activity during the reference period Spring 2020-2021 (Figure 1). Seven in ten of those online learners, corresponding to one in four EU+ adult workers, earned at least one certificate or award after completing an online education or training activity. This includes any credentials acquired by online learning providers, such as qualifications officially recognised by the relevant national education authorities or other online certificates of accomplishment and digital open badges, which are visual tokens and a verifiable record of a person’s learning and skills acquired online.

The largest shares of workers earning a credential or award following an online education or training activity is found in Southern European countries, including Ireland, Portugal, Greece, Spain, Italy and Lithuania. These are countries typically characterised by some of the highest qualification mismatch rates in Europe (Cedefop, 2022a), which may be indicative of the additional effort workers make in these countries to obtain further certificates of relevance for enhancing their employability and labour market prospects. However, the relatively high shares of workers earning certificates online in Luxembourg, Finland and Sweden also attests to the fact that their take-up reflects the degree of maturity in a country’s CVET and qualification system.

Workers employed in the primary sectors of agriculture, forestry or fishing, along with those in the secondary sectors of utilities (e.g. water and electricity supply) and in healthcare are most likely to have earned a certificate following an online training episode. Corresponding occupational groups, such as health professionals, health care workers, assemblers and builders, are more inclined to obtain digital credentials than others.

Among the self-selected group of adult workers who engaged in online learning, labour market status and job conditions are strong predictors of the likelihood of obtaining an accompanying certificate or award. Having recently made a school-to-work transition, or being employed in another job, improves the chances of following an online education or training course with accompanying certification. By contrast, the unemployed or inactive who decided to follow an online education or training activity are least likely to have gained a credential. This may reflect their limited resources and/or motivation to engage fully in a digital learning process that could lead to a formal credential. Workers who obtain a digital certificate are also typically in jobs with higher skill demands, particularly for elevated digital skills. While an individual’s level of formal education does not seem to drive attainment of credentials following online learning, being a VET graduate does so in a significant way. Given that workers who obtain online-mediated certificates are more likely to be in jobs experiencing new digital technologies/tools and higher skill demands, it is likely that VET graduates are faced with greater pressure than their non-VET counterparts to strive continuously to update their qualifications.

Digital credentials are only a part of the microcredentials story, though, as recently revealed by Cedefop’s dedicated study (Cedefop, 2023). Focusing on two main labour market sectors as part of Cedefop’s (2023) study provides interesting results. Manufacturing and retail are two of the largest sectors in the European Union, both in terms of their added value and their contribution to employment. However, at national level, the relative importance of these sectors in terms of employment varies. The detailed mapping and analysis of microcredentials in these sectors underlines that there are a range of certificates and certifications that are technical in nature and, at times, very specialised (see Table 1). Some are entry level certificates and certifications, while others are stacked and can support progression in the labour market from entry level jobs to technician and engineering level job roles.

Table 1 Microcredentials identified through Cedefop’s (2023) mapping exercise

|

Sector |

Title of microcredential |

Country |

|

Manufacturing |

Safety procedures in medical processes |

France |

|

Manufacturing |

Quality management system and welding coordination |

Denmark |

|

Manufacturing |

GMP and GDP certification |

Germany (and Europe-wide) |

|

Manufacturing |

International welding engineer (IWE) |

41 European and non-European countries |

|

Manufacturing |

International welding practitioner (IWP) |

41 European and non-European countries |

|

Manufacturing |

Qualification in additive manufacturing |

Offered by different providers in seven countries: France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Turkey and the UK |

|

Manufacturing |

Machine training courses |

Germany (Europe-wide) |

|

Manufacturing |

CNC specialist certificate |

Austria |

|

Manufacturing |

VET award in process manufacturing |

Malta |

|

Manufacturing |

3D printer operator for industrial applications |

Czechia |

|

Manufacturing |

Industrial health and safety advisor |

UK (England) |

|

Manufacturing |

International welding consultant |

Finland |

|

Manufacturing |

Robotic process automation fundamentals masterclass |

Ireland |

|

Manufacturing |

Working on an ammonia (NH3) installation safely |

France |

|

Manufacturing |

MAG welding with an electrode wire |

Poland |

|

Manufacturing |

Introduction to foundry technology |

Sweden |

|

Manufacturing |

Manufacturing operations for medical device/pharma industry (life sciences manufacturing operations) |

Ireland |

|

Manufacturing |

Supply chain manager – operational level |

Greece |

|

Retail |

Common food hygiene |

Denmark |

|

Retail |

Award in retail |

Malta |

|

Retail |

Sales for store employees |

Norway |

|

Retail |

Profitability of marketing and sales organisation in the luxury goods sector |

France |

|

Retail |

Award in retail operations |

Malta |

|

Retail |

Drugstore employee (DM Druggist) |

Slovenia |

|

Retail |

Fashion retail transformation |

France (and global-wide) |

|

Retail |

International e-commerce |

Sweden |

|

Retail |

Diploma course in retail management |

Global |

|

Retail |

Customer relationship management using CRM systems |

Poland |

|

Retail |

Award in credit for retail banking |

Malta |

|

Retail |

IKI training programme |

Lithuania |

|

Retail |

MAXIMA training programme |

Lithuania |

|

Retail |

Certified e-commerce & social media expert |

Austria |

|

Retail |

Merchant unit manager title |

France |

|

Retail |

Understanding retail operations |

United Kingdom |

|

Retail |

Specialist in retail sales |

Germany |

|

Retail |

Practical sales / merchandise knowledge |

Germany |

|

Retail |

Digital marketing |

Global |

|

Retail |

Non-formal vocational training programme in electronic cash registers and cash register systems management |

Lithuania |

|

Retail |

Marketing and sales techniques |

Greece (and global) |

NB: Even though the term microcredential is not always used, these examples can be considered microcredentials due to their characteristics and according to the stakeholders that participated in the consultation process. Source: Prepared by Cedefop, based on desk research, case studies, ReferNet questionnaires and interviews.

The retail sector is characterised by a large base of micro and small (often family) businesses, plus some large multi-national companies. The use of qualifications as a gateway to employment in the sector may be weaker than in manufacturing, where technical skill sets are more likely to be required. As a result, workers and self-employed business owners become attracted to microcredentials, as they are a way to upgrade their skills (Cedefop, 2022b). In manufacturing, in contrast, there are large variations between its different sub-sectors in terms of the production processes and levels of technology used, and hence the skills required. Supply chains can exert a strong influence on skills development.

The technical nature of these certifications and certificates generally suggests that they can function as top-ups to qualifications and added value for both learners and employers, though they may not be recognised in further learning. While some of these industry-related credentials provide reference to the EQF and formats of assessment, information about specific credentials varies substantially, and this contributes to additional fragmentation.

Yet the rapid developments taking place in manufacturing and retail suggest that employees in these sectors may need continuously to adjust their knowledge, skills and competences to remain employable within the relevant sector.

References

Cedefop (2020). Developing and matching skills in the online platform economy: findings on new forms of digital work and learning from Cedefop’s CrowdLearn study. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Cedefop reference series, 116.

Cedefop (2022a). Setting Europe on course for a human digital transition: new evidence from Cedefop’s second European skills and jobs survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Cedefop reference series; No 123.

Cedefop (2022b). Are microcredentials becoming a big deal? Cedefop briefing note, June 2022.

Cedefop (2023). Microcredentials for labour market education and training: microcredentials and evolving qualifications systems. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Cedefop research paper, No 89.

Kässi, O. and Vili Lehdonvirta (2021). Do Microcredentials Help New Workers Enter the Market? Evidence from an Online Labor Platform. Journal of Human Resources.

Footnotes

[1] Twago is distinctive because its profile page allows freelancers to upload PDFs of their certificates to help validate the skills they claim to have.

[2] E.g. PeoplePerHour’s CERT (Content-Engagement-Repeat Usage-Trust) system

|

Please cite this article as: Pouliou, Anastasia; Pouliakas, Konstantinos (2023). Labour market value of microcredentials: a conduit to better work? Thessaloniki: Cedefop |