In 2010, as part of its strategy for vocational education and training (VET) and lifelong learning, the European Union (EU) set out to achieve several statistical benchmark targets by 2020 (Box). The targets were ambitious and, in looking at the progress made towards achieving them, the statistical data paint a mixed picture of notable progress and discouraging setbacks.

Box: VET and related European statistical benchmark targets for 2020

|

Over the period 2010-20, the EU agreed the following quantitative benchmark targets related to vocational education and training (VET): |

|

|

Other VET-related quantitative benchmark targets agreed for 2020 were: |

|

The EU achieved two headline benchmark targets. First, it cut the proportion of early leavers from education and training in the EU to less than 10%. Second, it increased the proportion of 30 to 34-year-olds in the EU completing tertiary-level education to above 40%.

However, the EU did not meet its target of 15% of 25-to 64-year-olds participating in education and training. Participation in lifelong learning in 2020 was a disappointing 9.2% in 2020, but the figure for that year may have been reduced by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Aiming for an employment rate of 75% for those aged 20-64 years, the EU reached 72% in 2020. This was below the target but an improvement on the 69% recorded in 2015. The employment rate of recent graduates in the EU with at least an upper-secondary education also improved from 76.8% in 2010 to around 78.5% in 2020, but short of the of 82% target.

All benchmark targets were European averages, and the figures vary considerably between Member States. For example, the proportion of early leavers is 16% in Spain compared to 3.8% in Greece. Similarly, for example participation in lifelong learning is 20% in Denmark compared to 7.7% in Germany. Such differences between countries have existed for many years. Consequently, in 2010, Member States decided to what extent they could contribute to achieving the European benchmarks, and some set their own national targets for 2020.

The benchmark targets are only part of the story of European VET policy for 2010-20. They were quantitative targets set to support broader policy objectives to improve the quality of VET, align it more closely with labour market needs and to make VET an attractive learning option.

Benchmarks and indicators

Sound statistical information is essential to European VET policymaking and necessary for monitoring progress by the EU and its Member States towards agreed benchmarks. To support the monitoring process, Cedefop developed a framework of core indicators to observe statistical developments and trends. The framework grouped indicators into three key policy areas that reflected the overall aims of European VET and lifelong learning policy, namely:

- access, attractiveness and flexibility of initial and continuing VET

- investment, skill development and labour market relevance of VET; and

- labour market transitions and employment trends.

The framework evolved over time (see On the way to 2020, Cedefop 2013 and Cedefop 2017) and, included context indicators relating more broadly to the labour market. All indicators were selected according to their policy relevance and contribution to European VET policy objectives for 2020, as well as the availability, periodicity, comparability and quality of the data. This commentary covers 29 indicators, for which fresh data were available at the time of writing.

The indicators do not have a one-to-one relationship with different policy themes, nor do they assess national systems or policies. Instead, they provide a statistical overview of trends and developments that help describe and compare the progress of the EU and its Member States in implementing European VET policy.

Access to data for each indicator and a description of trends and developments, as well as definitions of the indicators and their data sources are available here. Indicator data, covers the EU, each Member State and, where available, Iceland, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Norway, Serbia, Switzerland, Turkey and the United Kingdom.

Indicator data are discussed below under each of the three policy areas in which the indicators were grouped. Although the policy cycle was 2010-20, the data discussed is from 2015-20. Methodological changes to the data, and breaks in time series, make the years 2015-20 the most reliable for comparing indicators within and between Member States. The period also coincides with a new revised set of European VET policy priorities for 2015-20, which were formulated in the Riga Conclusions in 2015.

Access, attractiveness and flexibility

A pillar of European VET training policy 2010-20 was to improve the attractiveness of VET as a learning option. The aim was to make access to VET easier and to improve opportunities for VET students and graduates to go on to further and higher education.

Participation is seen as a useful proxy for the attractiveness of initial and continuing VET as a learning option. Core indicators in this group cover participation by young people in initial VET and participation in continuing VET by various groups of adults, such as unemployed people, those with low levels of education and older workers (aged 50-64). The objective is to see not only levels of participation, but also how inclusive the VET system is. Indicators also look at training that enterprises provide for their employees to give a clearer picture of opportunities for participation.

Overall, VET in the EU seems to have maintained its levels of accessibility, attractiveness and flexibility. Initial VET systems aim to provide young people with skills and competences to access and make progress in the labour market. Participation in initial VET, in the EU overall, was stable at almost half of all enrolments in upper-secondary education at 48.7% in 2020, compared to 48.8% in 2015. Participation in initial VET is also considerably lower for female students in almost all countries with no major signs of change. Female participation in initial VET in the EU at 41.6% in 2020, was slightly down from 42.4% in 2015.

In the EU, some 70% of students in upper secondary VET were enrolled in programmes granting direct access to tertiary education in 2020, with most EU countries at or above 50%. However, this is less than the 72.7% in 2015. As in 2015, around a third of young VET graduates (18–24-year-olds with medium-level VET qualifications), were in further education and training in 2020.

Work-based learning can help transitions from education to work and develop relevant skills for the labour market. No benchmark target was set for work-based learning in initial VET in 2010. However, the Bruges communiqué of 2010 and the Riga conclusions of 2015 call for work-based learning to become a key feature of European initial VET systems.

Estimates are that, in 2020, around 29.6% of students in upper secondary VET were enrolled in combined work-and school-based programmes, where the work-based component is above 25% and below 90%. Many countries saw small increases in opportunities for work-based learning. Estimations of participation rates in work-based learning in initial VET vary and work is underway to improve the data. The Joint UNESCO, OECD, Eurostat (UOE) data collection on formal education systems indicates that around 30% of upper secondary VET students were enrolled in combined work- and school-based programmes in 2020. Preliminary findings of a Cedefop pilot study (see The role of work-based learning in VET and tertiary education, Cedefop 2021) which uses different definitions of work-based learning, indicate that over 60% of young recent VET graduates have had some work-based learning as part of their programme. This was confirmed by regular data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS), which is now available annually.

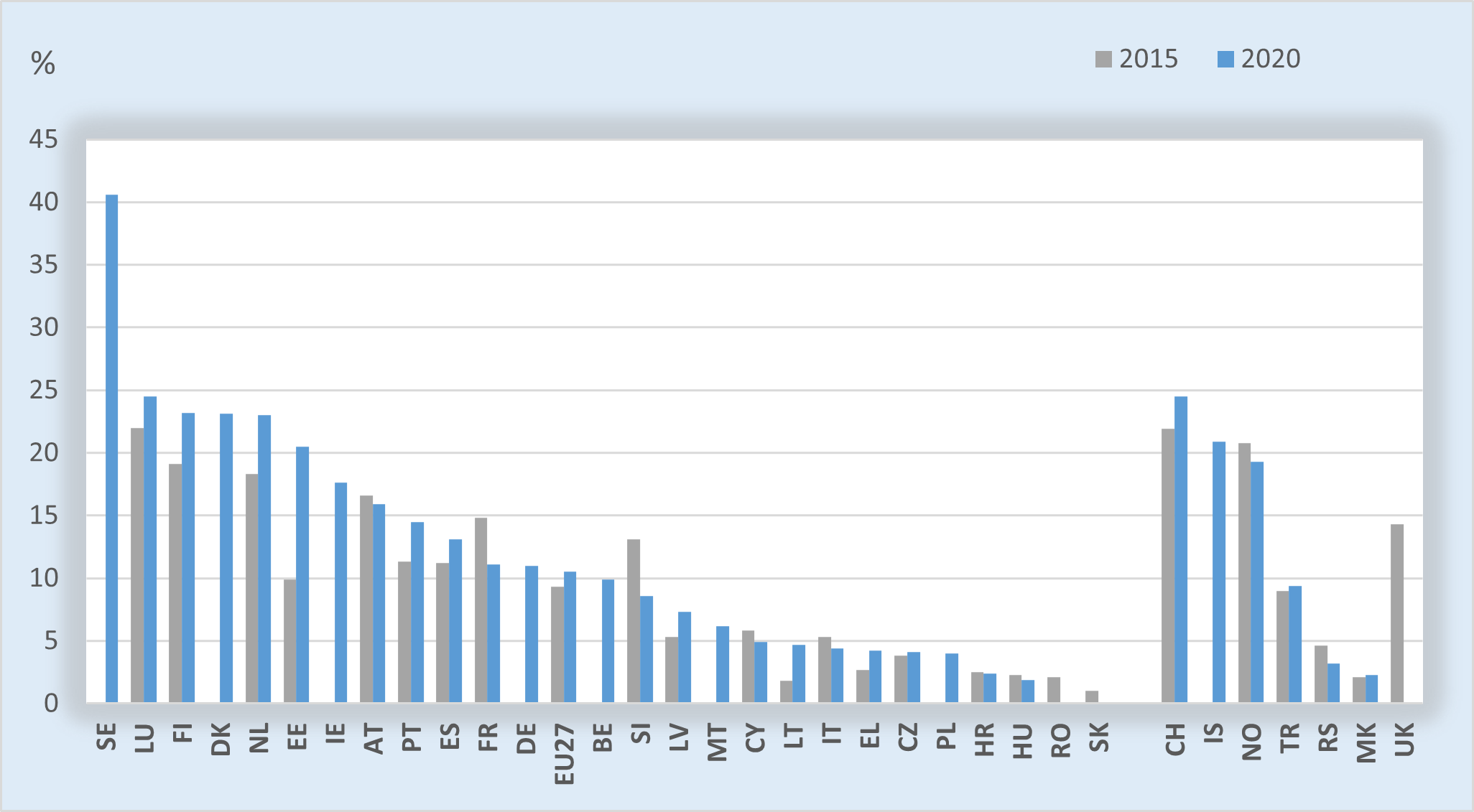

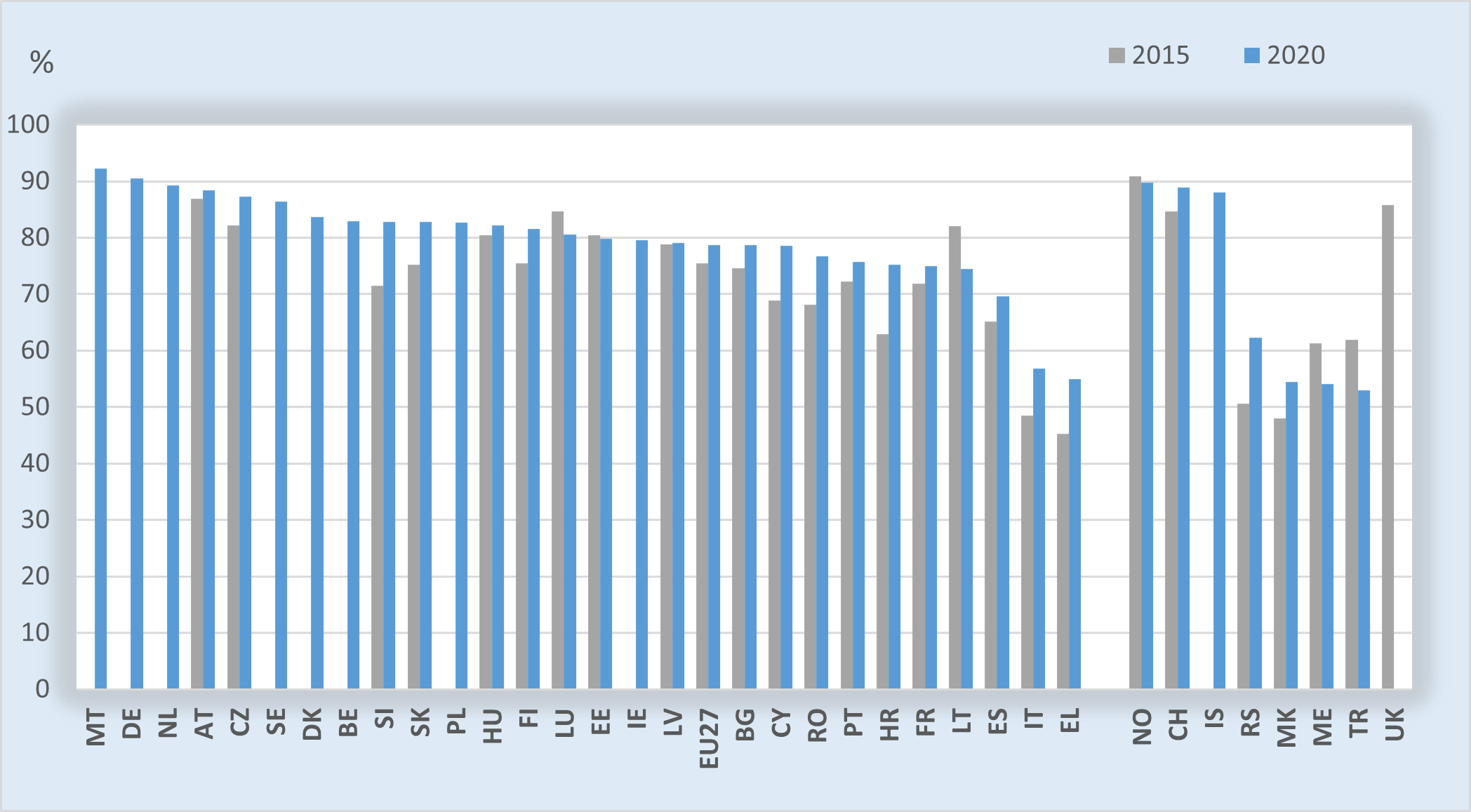

Raising participation in adult education and training has been a key objective of European VET policy since 2002. In that year, the EU set a benchmark target of 12.5% of adults aged 25 to 64 participating in education by 2010 but did not reach it. This target was revised to a participation rate of 15% by 2020, but again, overall, the EU fell short, although several Member States met or exceeded the target (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Unemployed adults’ participation in education and training: last 4 weeks (%)

Source: Eurostat, EU Labour Force Survey (LFS).

Although the Covid-19 pandemic may have lowered participation in lifelong learning in 2020, it does not seem to have prevented the EU from meeting its target. The high point of participation of adults in lifelong learning was 10.8% in 2019, well below the benchmark target, before falling back to 9.2% in 2020.

Participation rates of older (aged 50-64) and of low-educated adults in lifelong learning are well below the average of 9.2% for adults. Worryingly, older adult participation fell from 6.2% in 2015 to 2.6% in 2020, while participation of low-educated adults fell slightly from 4% in 2015, to 3.4% in 2020.

Employer sponsored continuing VET is a key component of adult learning, contributing to economic performance and competitiveness, as well as personal development and career progress. Continuing vocational training survey (CVTS) data, which are available every five years, reported that 67.4% of EU enterprises, employing 10 or more people, sponsored training for their staff in 2020. This is lower than the 70.5% in 2015. Similarly in 2020, in the EU, participation of enterprise staff in employer sponsored continuing training courses remained above 42% but was down by 0.5 percentage points compared to 2015. The falls in these figures, all of which relate to the year 2020, may be related to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Investment, skill development and labour market relevance

European VET policy 2010-20 aimed not only to stimulate skill development, but also to align VET more closely to labour market needs to improve people’s employment and career prospects. Core indicators in this group cover VET expenditure and VET’s contribution to different types of learning and educational attainment. Labour market relevance is observed by indicators focusing on the possible labour market benefits arising for those participating in initial and continuing VET.

VET expenditure is important but difficult to measure. Available data do not provide a comprehensive and integrated picture of public, private and individual expenditure on VET. For example, public expenditure on initial VET understates the contribution of employers, particularly in countries with dual system initial VET, such as Germany.

In a period marked by economic austerity, available data on public expenditure on initial and continuing VET show that it changed little during 2015-20. As a proportion of GDP, it was 0.51% in 2020, down slightly from 0.55% in 2015. However, expenditure per student, at Euro 7 900 (purchasing power standard) in 2020, was higher than the Euro 7 400 in 2015. Enterprises total monetary expenditure on continuing training courses for their staff was 0.8% of total labour costs in 2020, compared to 0.7% in 2015.

Indicators also look at VET’s contribution to developing skills in science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) related subjects, which are in demand on the labour market. In 2020, in the EU, 37.4% of upper secondary VET graduates obtained a qualification in STEM related subjects, slightly above the 36.6% in 2015.

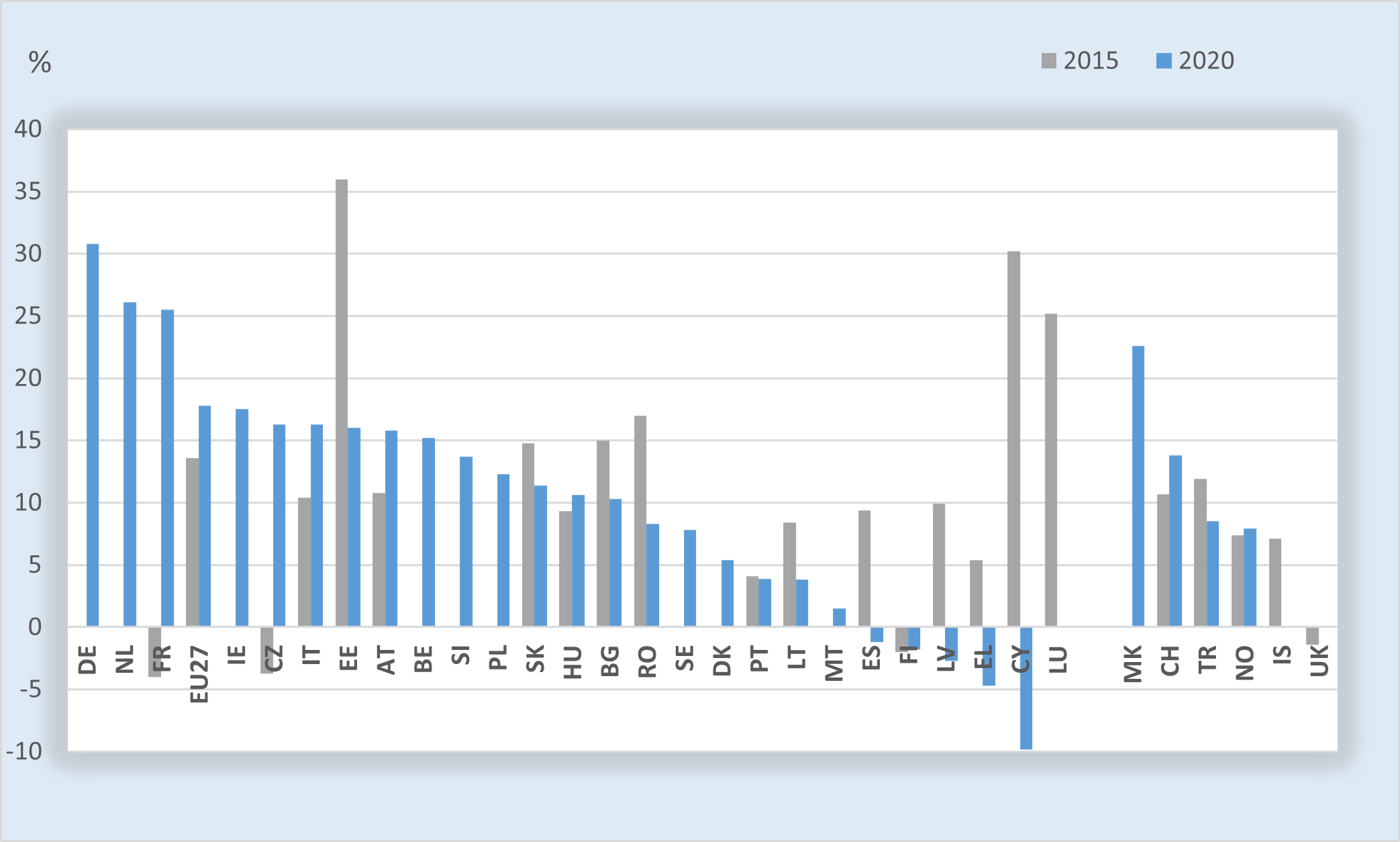

Concerning labour market relevance, employment prospects for VET graduates in the EU, which were already good, have improved between 2015 and 2020. Employment rates of recent VET graduates, aged 20- to 34-years-old, were significantly better - on average 17.4 percentage points higher in 2020 - than employment rates for general education graduates of the same age (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Employment premium for recent IVET graduates (over general stream) (%)

Source: Cedefop calculations based on Eurostat data, EU Labour Force Survey (LFS).

The EU benchmark target indicator on mobility of initial VET graduates for 2020 was for at least 6% of 18- to 34-year-olds with an initial VET qualification to have a related study or training period (including work placements) in another country. This indicator, however, proved impossible to measure accurately with current methodologies. However, the EU average number of foreign languages learned in upper secondary initial VET was 1.2 in 2020, lower than the average of 1.6 languages learned in upper secondary general education.

Overall transitions and labour market trends

VET needs to be understood in the context of the labour market in which it operates. Higher levels of qualifications are seen as equipping young people better with knowledge and skills to help their ‘transition’ from education and training to the labour market. Consequently, core indicators in this group, include the headline benchmark target indicators for reducing school leaving and raising educational attainment. Numbers of young people not in employment, education or training (the so-called NEETs) are also monitored. To observe labour market trends, this group also includes various employment rate indicators, including benchmark targets for the employment rates of 20- to 64-year-olds and of 20- to 34-year-old graduates.

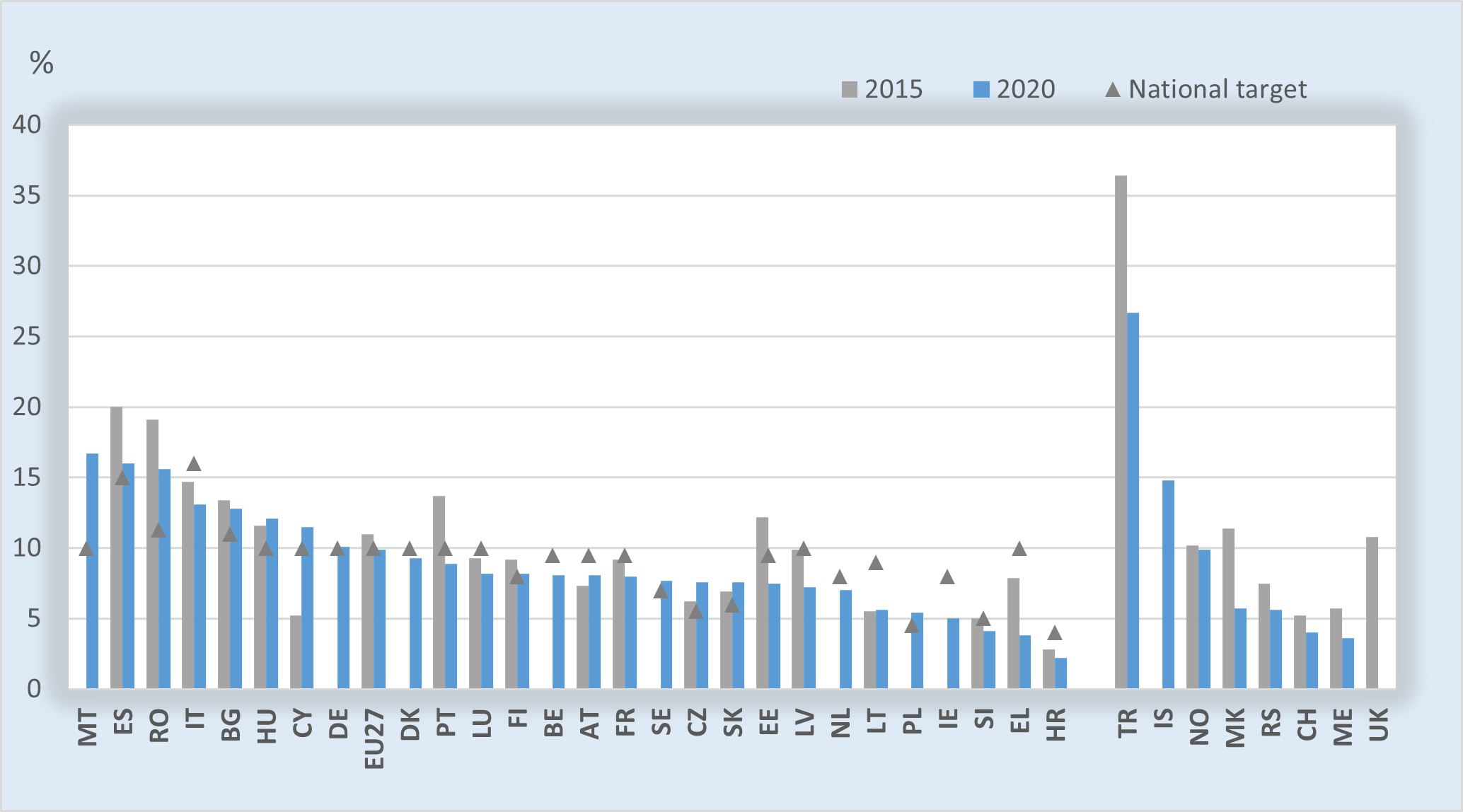

As discussed earlier, the EU achieved its headline benchmark target to cut the proportion of early leavers from education and training in the EU to less than 10%. From 13.8% in 2010, the share of early leavers from education and training in the EU fell steadily to 9.9% of 18- to 24-year-olds in 2020 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Early leavers from education and training (%)

Source: Eurostat, EU Labour Force Survey (LFS).

Although the EU did not set a specific target for 2020, another positive was that the proportion of young people NEETs fell from 15.2% in 2015, to 13.1% in 2020. Similarly, unemployment among 20- to 24-year-olds fell from 14% in 2015 to 10.4% in 2020.

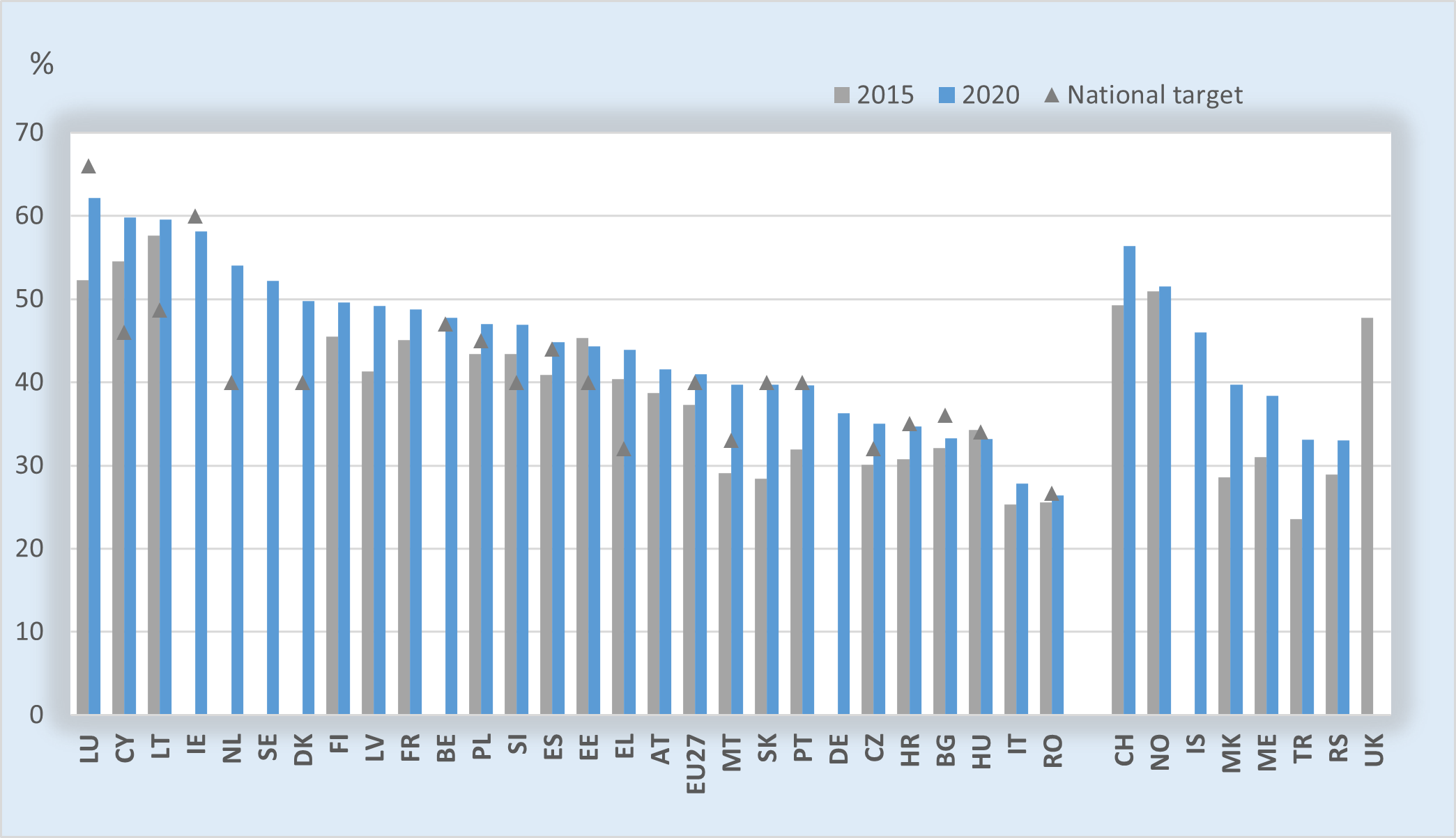

The EU also reached its benchmark target to increase the proportion of 30 to 34-year-olds in the EU completing tertiary-level education to above 40% (Figure 4). The figure reached 41% in 2020. Importantly, numbers of adults with low-levels of education fell consistently from nearly 24% of 25 to 64-year-olds in 2015, to 21% in 2020. It is important to note that while the youth unemployment rate is generally calculated and presented for those aged 15 to 24, the indicator focuses on 20- to 34-year-olds. This is to account for increasing numbers of young people who are staying longer in initial education and training, which is lowering labour market participation by 15- to 19-year-olds.

Figure 4. 30- to 34-year-olds with tertiary attainment (%)

Source: Eurostat, EU Labour Force Survey (LFS).

In 2020, the EU average employment rate for those aged 20 to 64 was 72.3%. This was below its benchmark target of 75%, but higher than the 69% in 2015 (Figure 5). The rate in 2020 may have been negatively affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, but it seems unlikely that the EU would have reached its target.

Similarly, the EU did not reach its benchmark target of 82% of young recent graduates, aged 20 to 34, being in a job in 2020. This figure reached 78.7% in the EU in 2020, an improvement on the 75.5% in 2015. Again, the Covid 19 pandemic may have lowered the 2020 figure.

Figure 5. Employment rate of recent graduates (%)

Source: Eurostat, EU Labour Force Survey (LFS).

The final indicator in this group underlines the importance of skills and qualifications for finding a job in today’s labour market. In 2020, in the EU, individuals with medium-and high-level qualifications accounted for 84.2% of total employment, with only 15.8% of jobs occupied by those with low qualifications.

2020: Before and after

The statistical data paint a picture of mixed achievement in terms of reaching the benchmark targets and other aims of European VET policy between 2010-20. Progress has been made in many areas and in many countries, even if benchmark targets have not been achieved, but there has been little or no movement on some important VET policy aspects.

The data show that, in statistical terms, the EU made substantial progress in raising educational attainment and reducing the proportion of young people leaving education and training early and with low or no qualifications. However, participation by adults, particularly older adults, in lifelong learning, remains stubbornly low. Investment in VET by employers seems to have been broadly stable, despite the growing demand for skills. More positively, investment has not fallen during a period of economic austerity and the CVTS data, which relates to 2020, may have captured lower levels of investment in that year due to the economic shock of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Employment rates have also improved. Failure to reach the target rates has more to do with overall economic growth than specific education and training policy. However, in terms of alignment, VET graduates seem to be in demand, but this does not seem to have translated into higher levels of participation in initial VET.

Benchmark targets and Cedefop’s core indicator framework have shown the value of using statistical data to provide information on trends to develop European VET and lifelong learning policies. Trends revealed by the data and the experience of the period 2010-20, have informed the setting of new benchmark targets for the post-2020 European VET policy cycle.

The focus of new benchmark targets for the post-2020 policy cycle is on areas where the EU underperformed in the previous period, namely participation by adults in lifelong learning and mobility. New methods are being developed to measure progress in these areas. The EU has also set a specific benchmark target for the employment rate of VET graduates aged between 20-34. There are also benchmark targets for participation by VET students in workplace learning and for the proportion of adults having basic digital skills.

Achieving these benchmark targets is seen as important for three key policy priorities, namely strengthening the EU’s economic and social resilience and sustainability, supporting people’s job and career prospects and creating a lifelong learning culture, where people seek to learn continually.

To monitor progress specifically towards the benchmark targets, Cedefop has set up a European VET policy dashboard, while a more broader statistical picture of developments and trends can be found from Cedefop’s Key indicators on VET.

List of abbreviations

|

CVTS |

Continuing Vocational Training Survey |

|

ISCED |

International Standard Classification of Education |

|

LFS |

European Union labour force survey |

|

NEET |

Not in employment, education or training |

|

UOE |

Unesco OECD Eurostat Joint data collection on formal education |

List of indicators

Access, attractiveness and flexibility

- Indicator 1. IVET students as % of all upper secondary students

- Indicator 2. IVET work-based students as % of all upper secondary IVET

- Indicator 3. IVET students in programmes with direct access to tertiary education as % of all upper secondary IVET

- Indicator 4. Workers participating in CVT courses (% of employed)

- Indicator 5. Adults’ participation in education and training- last 4 weeks (%)

- Indicator 6. Enterprises sponsoring training (%)

- Indicator 7. Female IVET students as % of all female upper secondary students

- Indicator 8. Workers in small firms participating in CVT courses (%)

- Indicator 9. Young VET graduates in further education and training (%)

- Indicator 10. Older adults’ participation in education and training – last 4 weeks (%)

- Indicator 11. Low-educated adults’ participation in education and training – last 4 weeks (%)

- Indicator 12. Unemployed adults’ participation in education and training - last 4 weeks (%)

Investment, skill development and labour market relevance

- Indicator 13. IVET public expenditure (% of GDP)

- Indicator 14. IVET public expenditure per student (1000s PPS)

- Indicator 15. Enterprise total monetary expenditure on CVT courses as share of total labour cost (%)

- Indicator 16. Average number of foreign languages learned in initial VET

- Indicator 17. STEM graduates from upper secondary VET (% of total)

- Indicator 18. Short-cycle VET graduates as % of first-time tertiary level graduates

- Indicator 19. Employment rate for recent IVET graduates (20–34-year-olds)

- Indicator 20. Employment premium for recent IVET graduates (over general stream) (%)

Overall transitions and labour market trends

- Indicator 21. Early leavers from education and training (%)

- Indicator 22. 30- to 34-year-olds with tertiary attainment (%)

- Indicator 23. NEET rate for 15- to 29-year-olds (%)

- Indicator 24. Unemployment rate of 20- to 34-year-olds (%)

- Indicator 25. Employment rate of recent graduates (%)

- Indicator 26. Adults with lower level of educational attainment (%)

- Indicator 27. Employment rate for 20–64-year-olds (%)

- Indicator 28. Employment rate for 20–64-year-olds with lower level of educational attainment (%)

- Indicator 29. Employment of those with medium/high level qualifications (as a percentage of total employment)

Data insights details

Downloads

Indicator sources, descriptions and methodology